Eastern Mediterranean Gas: Financial Windfall or Geopolitical Trap?

14 Oct 2020

The Turkish Navy has announced that the Oruc Reis, a research ship at the centre of the energy rights dispute with Greece, is set to be deployed back to the eastern Mediterranean to conduct seismic research. In August, tensions were sparked when this vessel was sent to conduct a similar survey in an area claimed by Greece, Turkey and Cyprus. For more insight into the dispute and the potentially lucrative discovery under the sea, please give the advisory a read.

Executive Summary

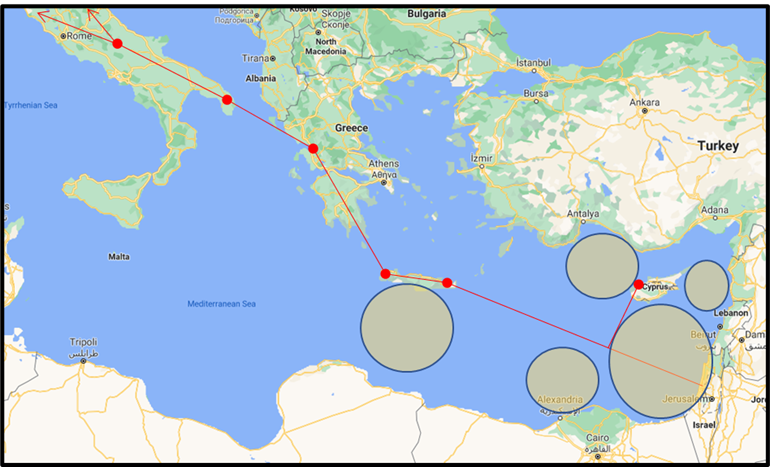

The last ten years have seen the discovery of large potentially viable reserves of natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean off the coasts of Israel, Cyprus and Libya. These discoveries have only served to inflame a number of ongoing disagreements in the region. Most notable of these being the dispute between Greece and Turkey over both the control of the Aegean Sea and over the status of Cyprus. Other issues complicated by the gas discoveries include the maritime border dispute between Lebanon and Israel and the ongoing Libyan Civil War.

The discoveries have also sparked a new “Great Game” in the area between the Mediterranean’s largest powers, Italy, France, Turkey and Egypt. These four countries between them hold half of the Mediterranean’s population, and are vying for control over large proportions of the region’s resources and commercial routes. Two of them are also EU member states with the associated political advantages that this brings.

In January 2019, the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) was set up comprising of Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and Palestine, but crucially, Turkey was not included. This absence from the body, established ostensibly to discuss how to increase regional cooperation in relation to the gas discoveries, only increased tensions. The EMGF also has ambitions to create a regional gas market.

Both the EU and NATO are currently working on trying to find a settlement to the newly inflamed tensions, in particular the ones between Greece and Turkey. However, the discovery of gas is likely to pose new challenges and continue to impact an already volatile part of the world, with effects being felt in countries such as Belarus, over the issues of sanctions against the Lukashenko government, and Libya.

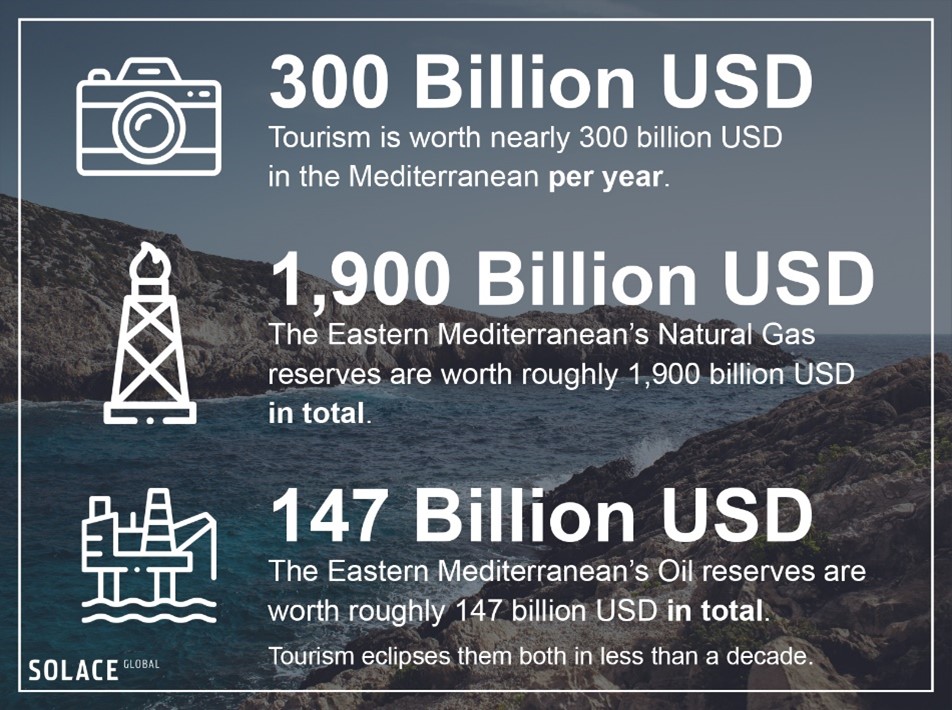

Despite the geopolitical manoeuvring from a variety of powers, there remain large questions over the viability of gas reserves in an area renowned for its tourism industry, and as the world begins to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels as part of global commitments to climate change. The answers to these two key questions likely mean that the viability of the gas reserves is less than most nations in the area would hope for, and that the current escalation in tensions is akin to performative theatre.

A Gas Filled Future?

The first major discoveries, the Tamar and Leviathan gas fields, were discovered off the coast of Israel. This was followed by the discovery of the Aphrodite field off the Cypriot coast. These early discoveries were dwarfed in 2015, when the Italian energy firm ENI announced it had found the largest ever gas field in the Mediterranean at what became known as the Zhor gas field. The Zohr gas field began to export its first gas in 2017, an event hailed as a milestone for Eastern Mediterranean gas ambitions.

The countries currently involved in the EMGF control a significant portion of global gas reserves and hold a dominant 87% share of all the gas finds in the Mediterranean. If they so choose to, the EMGF could become a market price setter, similar to how OPEC is with oil. To do this, at least one of the larger gas exporting states such as Iran, Norway, Qatar or Russia would need to join. Iran and Russia are unlikely to join, as the EMGF presents a risk to their own gas exports. It would make sense for Qatar to join a group of gas producers, especially given the rift that exists between Qatar and Saudi Arabia and the fact that Qatar left OPEC in 2019. However, Qatar, which is loosely aligned with Turkey on a number of matters may not consider joining the EMGF until the ongoing disputes between EMGF members and Turkey have been satisfactorily resolved.

Israel has already benefitted from the gas discovered in its EEZ. The EMGF is the first time that Arab states in the region have included Israel as an equal partner in a regional grouping. Such a public partnership builds on the ongoing process of normalization of ties between Israel and her gulf and Arab neighbours, potentially heralding a new age of regional cooperation. Further to this, the Israeli’s have signed a fifteen-year agreement valued at USD 19 billion to supply their gas to Egypt, a deal both sides admit is the most significant since the 1979 peace deal. In a sign of further Israeli – Arab cooperation, they have also agreed to supply gas to Jordan.

Despite this promising start, the desire for Eastern Mediterranean gas to ever become as financially lucrative as the involved states may hope is unlikely. Firstly, there is the financial impact of COVID on international Oil and Gas majors. The pandemic has caused significant declines in the prices of oil and gas. This in turn has led to significant cost-cutting at international oil and gas companies, as they write down and re-appraise the value of their assets and call a halt to expensive exploration projects. As part of the latter trend, a number of proposals in the Eastern Mediterranean basin have been postponed or cancelled, such as drills off the coast of Lebanon and Cyprus. This makes it unlikely that there will be any further immediate development of the Eastern Mediterranean gas fields.

Then there is the fact that the region has an extensive and important tourism industry, which could be damaged by any moves to commercially extract large quantities of gas. The Mediterranean recorded nearly one-third of all tourism worldwide and earned EUR 217 billion in international tourism receipts, which equates to 23% of the world’s total tourism revenue. Extractive industries could severely jeopardise some of the main drivers of this industry, such as clean beaches, waters, thriving ecosystems, and undisturbed traditional settlements and ways of life.

Finally, there are the inter-correlated reasons of climate change and greater use of renewable energy sources. Most European gas markets are in the middle of decarbonisation strategies, making any long-term reliance on new fossil fuels politically toxic in the region. Recent years have also seen the “green credentials” of gas shattered, with a number of reports now highlighting the amounts of methane now released during the extraction of natural gas make it substantially worse than coal for the environment. Alongside this, by the time any Mediterranean gas reaches the market, green policies such as carbon taxes would likely severely hamper the price of natural gas. The price competition of gas is also hindered by the fact that often renewable sources of energy generation are now cheaper than their fossil fuel counterparts. The falling price of renewables globally should lead to questions being posed as to why the Mediterranean region, with immensely favourable conditions for clean energy generation, is focusing resources on hard and expensive to extract gas, when instead they could be looking to set themselves up as energy providers of the future with their renewable resources.

Greece & Turkey

The discovery of gas has served to inflame tensions between Greece and Turkey, with the latter accused of conducting illegal drilling and prospecting in Greek territorial waters. The EU and several other states are backing the Greek position, whilst Turkey continues to insist it is in the right. To try and diffuse the tension, NATO has been holding technical talks between the partners. Delegations from the Greek and Turkish militaries attended the sixth round on 29 September 2020 at NATO HQ in Brussels. Alongside the NATO talks, Germany is leading talks between the EU and Turkey which hold the prospect of an enhanced customs union between Turkey and the EU, if they agree to back down from their aggressive stance in the Mediterranean.

At the current time of writing, the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) pointedly excludes Turkey, and in response, Turkey has called the forum an “alliance of malice”. Such a move hinders any meaningful long-term cooperation; consequently, the invitation of Turkey into the EMGF may be a positive step towards diffusing tensions.

The EU is also working to try and solve the tensions between the two states and will likely try to find a compromise that saves face for both sides. Eastern European states are wary of antagonising Turkey, which possesses the largest standing army in NATO after the US. For them, Turkey is a bulwark against further Russian adventurism on Europe’s eastern front. This divide between how the Eastern EU and Southern EU view Turkey was illustrated on 21 September, when Cyprus used its veto to hold up pending EU sanctions on Belarus until the EU imposes similar sanctions on Turkey. Germany is trying to use the offer of an enhanced customs union between the EU and Turkey as an incentive for Turkey to drop its aggressive stance. Despite this, recent divergences in EU and Turkish politics and priorities indicate that that growing distance between the EU and Turkey is not an aberration and that further estrangement could occur.

A New Great Game

Traditionally, and historically, France and Italy were both strategic rivals in the Mediterranean. This rivalry plays out in numerous ways today. For instance, Italy has backed the Libyan Government of National Accord, whilst France has backed the rival eastern Libyan National Army. Further to this, French and Italian oil and gas supermajors, Total and ENI respectively, are both rivals in North African oil and gas industry. There is also the fact that both nations often vie to be seen as the spokesperson for the Mediterranean region within the EU.

On top of this, due to historical and commercial links, Italy has always had a close relationship with Libya, its neighbour and former colony to the south, whilst France has always historically been more interested in the French-speaking African Maghreb. Recent Turkish moves to shore up the Government of National Accord (GNA) has changed this dynamic. Turkish support for the GNA enables Ankara to drill for oil and gas off the Libyan coast, and to effectively prevent the building of an undersea pipeline to connect the various eastern Mediterranean gas fields to the European market. Such support also renders Italian assets in Libya vulnerable to potential Turkish pressure and could likely lead to a closing alignment of French and Italian Mediterranean strategies.

The establishment of a new Paris – Rome corridor in the region would lead to a wholesale realignment within the region’s geopolitics and have profound consequences. Perhaps sensing the implications of this. French President Macron has called for a “Pax Mediterranea” managed by a partnership of the EU’s Mediterranean nations.

Egypt is likely to be the main beneficiary of any solid moves to extract gas from the eastern Mediterranean basin. The fact that the largest find so far, the Zohr field, is in Egyptian waters and the fact that the country has existing gas facilities, means they have the potential to develop a strategic energy hub in Cairo, and to become a gas capital for the region, an ambition that is well on its way to coming to fruition with the HQ of the EMGF being located in Cairo.

For the European Union, if it can sort out the competing claims in the Eastern Mediterranean and diffuse the situation, then having large scale natural gas exporters, some of whom are members and allies will be a boon. They will be able to diversify their natural gas supplies using nearby natural gas reserves, in order to reduce dependence on Russia which currently supplies about one-third of the European Union’s crude oil and 39% of gas imports. This reliance on Russian gas is seen by a number of EU nations as a security risk especially as Russia becomes more aggressive in its posture towards the west. Potentially Eastern Mediterranean gas reserves should more than meet European gas needs into the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

Whilst the attraction of possibly becoming a key player in the international energy arena, and with large oil majors still interested in the region due to being shut out of other arenas through pro-green energy policies, allowing drilling in this area is likely to be tempting for the Eastern Mediterranean.

It would, however, be an expensive and false promise, which will continue to lead to escalating tensions, and could serve to undermine the region’s vital tourism industry. Instead, states in the region wishing to become energy exporters should seek to use their abundant renewable resources, which will likely prove in the long term to also be a sounder financial and geopolitical choice. This is as opposed to the current trajectory which would see the exploitation of these reserves purely for nationalistic purposes with little attention paid to the proposed economic returns, or lack of them, on the large-scale investments needed.

Whilst it is unlikely that the tensions in the region will be diffused quickly, with so much perceived to be a stake, there are a number of avenues already being explored which could longer-term be part of the solution. These include the admittance of Turkey into the EMGF, possibly also the enhanced EU-Turkey customs arrangement proposed by Germany, and potential international arbitration over the disputed maritime borders in the region. Any re-alignment of the currently opposing Italy and French positions on Libya, is likely to lead to a shift on the wider EU position on the North African country, which longer-term may help lead to the beginnings of a resolution in the country, but there are so many external players in the conflict this is unlikely to occur with any rapidity.

Finally, a resolution on issues in the Eastern Mediterranean in a manner seen as favourable to all parties will likely lead to the unblocking of wider EU measures on the issues of Belarus and its widely disputed general election, showing the domino effect the region could potentially have on the wider European continent.