Evacuations from Israel and High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

West African Democracy and Security: Progress or Regression?

1 Dec 2020

This is our first report in a miniseries exploring some of the problems West Africa faces as it grapples with increasing problems in democracy and security. This first part will primarily look at how two recent elections, in the Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea, embody the recent democratic declines that much of the region as a whole is experiencing.

Executive Summary

This is our first report in a miniseries exploring some of the problems West Africa faces as it grapples with increasing problems in democracy and security. This first part will primarily look at how two recent elections, in the Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea, embody the recent democratic declines that much of the region as a whole is experiencing.

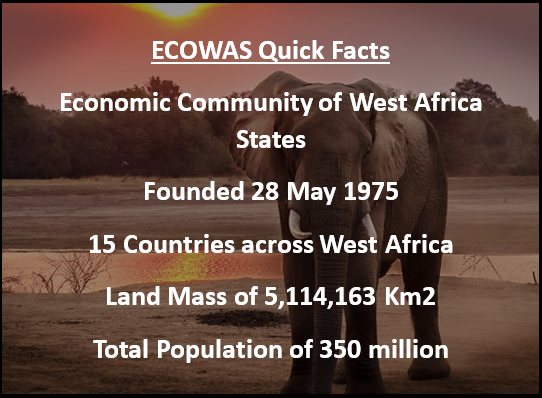

The West African region is defined by the United Nations as 16 countries, including, Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Benin, Burkina Faso and Guinea. The region’s population is around 380 million. A number of countries in this region are part of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which has a total GDP of USD 716.7 billion. The largest state in West Africa is Nigeria, which is often seen as a key regional power.

In the last three decades, the region was hailed as leading Africa’s transition from authoritarianism to democracy. Across West Africa, a number of countries emerged from military or dictatorial rule, and political parties and open debate began to flourish. A number of countries then began to witness reasonably stable transfers of power and leaderships. All of this gave hope that democratic norms were slowly becoming embedded in the region, which could provide a showcase of vibrant pluralistic African democracies to other African countries which were less democratic.

However, in the last half-decade or so, there is increasing concern that much of this work is slowly being unravelled. The emerging democratic norms have turned out to be less permanent and embedded than perhaps western analysts hoped.

The first indication of the regions increasing democratic decline can be seen from the fact that in the 2019 edition of Freedom House’s rankings of Democracies, 5 of the 12 worst performers are all located in West Africa, these are Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali and Nigeria. Alongside this, both Senegal and Benin fell from the “Free” category to being “partially Free”, which means the only continental country in the region ranked as free is Ghana. Cape Verde, The UK Ascension Islands and Sao Tomé and Principe are all however also ranked as free.

A Tale of Two Elections

As stated, nothing emphasises the issues surrounding the democratic decline in the West Africa region more than the recent two elections held in Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire. Both elections initially resulted in widespread protests, and the death of some protest leaders. In both cases, the elections were the culmination of anti-democratic tendencies that had been building over the last 12 months. Alongside this, the rising anti-democratic climate in both countries has followed a similar path.

Guinea

Since its independence from France in 1958, Guinea has had periods of authoritarian rule, military rule and stable democracy, and has only had six leaders, of which two, Ahmed Sekou Tourre (1958 – 1984) and Lansana Conte (1984 -2008), served for a combined over fifty years. These years were also marked by mass killings, persecutions of dissidents and, at one point, a ban on all private economic transactions. On Tourre’s death in 1984, a bloodless military coup took place which brought Conte to power where he remained until his death in 2008.

It was not until 2010 that Guinea was to see its first free and fair democratic election. For many, it was seen as a chance for Guinea to chart its own path out of authoritarian rule. The election included 24 candidates and in the first round, no-one won an outright victory, and so there was a second-round run-off vote between Alpha Conde and Cellou Dalein Diallo.

The election was marred by voting rigging scandals, violence and potential corruption. Two officials from the National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI), including the then President of the Commission Ben Sekou Sylla, were accused of vote tampering during the first round, this news plus rising tensions between supports of different candidates resulted in the 2nd round being delayed until November. Over the course of the 2010 election riots, clashes were common occurrences; 170 were arrested and 24 injured during one round of notable clashes between supporters of the two rival candidates. As it became clear that Conde had won, Diallo announced that he would not accept the provisional results until a number of irregularities had been looked at. In December, after the results had been certified by CENI and Diallo’s challenges rejected by the Supreme Court he announced his concession and called for calm. Despite the clashes, this marked the first free election in the country and international observers stated the election was credible and fair.

The 2015 election built upon this promising start. Eight political parties contested the election, and Conde won in the first round with 58 percent of the vote. International observers were present and whilst they stated that the pre-election process had “deficiencies”, the election overall and the result could both be considered valid. Diallo once more stated his intent to challenge the results; however, the nation’s courts found the challenge unfounded and declared that Conde had been re-elected. Since his re-election in 2015, observers have noted that Code has increasingly become authoritarian in his measures, and this culminated in a controversial constitutional amendment which he pushed through in March. He has also taken to replacing the heads of a number of national bodies who opposed him with loyalists, the shutting down of media companies and arrests of those seen as opposition leaders.

The amendment was nominally backed by the public in a referendum. However, the vote was marred by severe violence which led to 32 being killed, election workers being kidnapped, and a widespread opposition boycott of the vote. Following the referendum, the UK, UN and the EU all issued warnings over the fairness and credibility of the referendum.

There were fears that Conde may try to use the new amendment as an excuse to “reset” his term limit, and potentially be president for another 12 years which meant he could still be president at the age of 93. These fears were realised in August, when it was announced that Conde was officially running in the 2020 election for a third term.

Against this backdrop then, and rising authoritarianism and political oppression, it is perhaps therefore unsurprising that the presidential election held on 18 October was also seen as being controversial. Both Conde and his main opposition candidate, Dalein Diallo (for a third time) claimed victory. There have also been large scale protests and demonstrations against Conde. On polling day alone, it is believed that 20 were killed and more than 100 injured. Alongside this, for the first two weeks after the election, Diallo was placed under house arrest and it was reported that there was an overbearing security presence in areas that voted strongly for Diallo.

This makes it difficult to ascertain who may have actually won the election. According to officials, Conde won with 59 percent of the vote. However, four electoral commissioners, who are also linked to the Diallo opposition, have released a report from the commission which details “serious irregularities” that took place in the election. These irregularities include issues such as turnout being more than 100 percent in some government strongholds. While the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) sent an election delegation to the country to try and offer support, for many in the opposition, the election monitors have lost credibility after being silent in the aftermath of the controversial constitutional changes in March. Both the European Union and the US State Department have released statements questioning the integrity of the election.

This makes it difficult to ascertain who may have actually won the election. According to officials, Conde won with 59 percent of the vote. However, four electoral commissioners, who are also linked to the Diallo opposition, have released a report from the commission which details “serious irregularities” that took place in the election. These irregularities include issues such as turnout being more than 100 percent in some government strongholds. While the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) sent an election delegation to the country to try and offer support, for many in the opposition, the election monitors have lost credibility after being silent in the aftermath of the controversial constitutional changes in March. Both the European Union and the US State Department have released statements questioning the integrity of the election.

Diallo once again took his case to the constitutional court. On 8 November, it was reported that the Supreme court of Guinea had approved the victory of President Conde. They stated that they had examined objections from four other candidates, including Diallo, and decided that they were unreasonable. The court also updated Conde’s vote total from 50.49 percent to 59.50 percent. Thus, it looks at the current time as though Conde may well be on course to be President of Guinea until he is 92. Diallo has also been since accused of post-election violence, which is an indictable crime in Guinea.

Cote d’Ivoire

A similar dynamic is currently playing out in Cote d’Ivoire, after President Alassane Ouattara won a third consecutive term in office in the elections on 31 October, which were widely boycotted by the opposition. Ouattara had initially promised to step down from office after the end of his second term. This was initially hailed as a democratic milestone in the country that was still recovering from the ravages of the two deadly civil wars which pitted the North and the South of the country against one another. The second civil war had, incidentally, been sparked by the 2010 disputed Presidential election which saw the then opposition leader, Alassane Ouattara, win at the ballot box, before the President of the Constitutional Council (CC) declared the result invalid and declared the incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo the winner. Ouattara, who was supported by the UN, ECOWAS, the EU, the US and the AU, eventually won the resulting civil war and acceded to the Presidency.

The 2015 election, by comparison, was credited as being simple, fair and valid by international observers, despite some opposition members urging a boycott of the election. The success of this election raised hopes that the country was turning a corner on its recent bloody past and was slowly transitioning to become a peaceful and democratic state. Such hopes were further buttressed in 2020 when Ouattara announced in March that he would not be running for a third term, and that he would be respecting the two-term limit set out in the country’s constitution. In doing so he seemed to reject the increasing prevalence in the region for “third-termism” as seen in Guinea, and previously used by the President of the Republic of Congo. Instead, Ouattara nominated someone he wished to run as his successor, the then prime minister, Amadou Gon Coulibaly.

However, it all changed after the death of Coulibaly. Ouattara then claimed that due to a constitutional amendment in 2016, he could, and would run for a third term. Ouattara won the election with a supposed 94 percent of the vote.

Even before the vote took place, at least 30 people were left dead in instances of political violence between opposing sides, and on election day itself a further five were killed, and the two main opposition candidates announced that their houses had been fired upon. This has no doubt invoked memories of the 2010 Presidential election in the country in which the post-election war is estimated to have killed 3,000 people. It is also being reported that many Ivorian’s have crossed over into neighbouring countries such as Ghana, Liberia and Togo. In the days after the election, riot police surrounded the homes of opposition leaders, effectively placing them under house arrest; a number of machete attacks between rival political camps across the country have been reported. Finally, a vehicle convoy of the government minister for communications, Sidi Toure, was fired upon which resulted in the death of one of his convoy members.

In the aftermath of the Ivorian election, one of the leading opposition figures and former Prime Minister Pascal Affi N’Guessan, claimed the result was illegitimate stating that: “This was a sham election … marred by many irregularities and a low turnout”. He then further announced that the opposition’s leaders and parties would be forming an alternative “transitional government”.

In the wake of the announcement of the formation of the parallel “transitional government”, it was announced on 7 November that the N’Guessan had been arrested for sedition. It was also announced that a number of other opposition leaders and figures have also been arrested on similar charges, such as sedition or terrorism, after rejecting the re-election of Ouattara. Since the imprisonment of N’Guessan, there have been further violent instances of unrest in the country with reports that violence is distributed across the country, with machetes and rifles being used in attacks on rival supporters. It is now believed that post-election violence in the country has led to the deaths of around 85 people and injuring nearly 500 others.

Ultimately, all these moves have changed the regional and global view of Ouattara. In 2015, in the aftermath of that year’s elections, he was seen as the new champion of West African democracy. The October election, however, is now seen by many as the culmination of numerous authoritarian moves made by the president. For example, even before the vote, in 2019, he forced his main rival into exile, after issuing an arrest warrant for his supposed involvement in a coup attempt. This was then swiftly followed by the imprisonment of numerous other civil society actors and opposition leaders who had criticised his premiership. His third term, set against this backdrop, is less a spontaneous move and more the culmination of a slowly building authoritarian policy.

Conclusion

Both Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire entered the last decade with fragile democracies that international observers were hopeful could sustain the progress made since the mid-2000s. However, as outlined, hopes have certainly been dissipated in the wake of the two elections the countries held in 2020.

In both Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire, both current presidents could have abided by their constitutional term limits and helped solidify their countries fragile democratic norms, instead they appear to have struck out on less democratic paths, or paths of “third-termism”. Third termism, which is literally the practice of seeking a third term despite term limits, is seen in many quarters as “Africa’s constitutional failure” in the wake of the success of blocking third terms in Nigeria (2006) and Burkina Faso (2014).

As a result, both Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire will likely suffer increased political insecurity, while other leaders in the wider region now have a blueprint on how to discard democratic norms and processes. In part 2 of our mini-series, we will look to explore how the democratic decline in these two countries is indicative of wider regional democratic malaise, and associated insecurity that is rife throughout West Africa.

This decline has come as something as a shock given that by the early-mid-2000s, every major country in Africa, apart from Eritrea, and Swaziland had acknowledged the commitment (at least in principle) to holding competitive elections and transfers of power. Perhaps then the wider decline in West Africa, is itself a symptom of a more worrying continental shift towards a resurgence in authoritarianism. All of this and more will be looked at in Part 2.

Continue Reading

West African Democracy and Security Part 2: The Region Undergoes a Backwards Slide

West African Democracy and Security Part 3: The Rise of Insecurity

The Sahel Deterioration and Violence in West Africa in 2024

Explore the democratic decline in West Africa, driven by factors like aging leadership, evolving ECOWAS goals, and Beijing’s influence through loans. We also examine Ghana’s position within this context, pondering if it bucks the regional trend or shares in the backward slide.

Examine the intertwining of the security decline in the region with escalating insecurity, where each contributing factor fuels the other in a concerning cycle.

The Sahel, characterised by growing instability triggered by poverty, food insecurity, water scarcity and challenges presented by terrorism, rebel groups and poor governance, faces threats of further deterioration of security in 2024.