Evacuations from High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

West African Democracy and Security Part 3: Rise of Insecurity

24 Feb 2021

This is the final instalment in a mini-series that has been focused on West Africa. Part one focused on two recent elections and what they could signify, part two looked at the democratic decline the region was facing. This part looks at how the democratic decline has coincided with rising insecurity, with both now becoming drivers for each other.

Executive Summary

This is the final instalment in a mini-series that has been focused on West Africa. Part one focused on two recent elections and what they could signify, part two looked at the democratic decline the region was facing. This part looks at how the democratic decline has coincided with rising insecurity, with both now becoming drivers for each other.

This insecurity has plagued the region for a number of years now. On land, despite the intervention of European countries to try and stabilise the region, and at sea, despite regional and multinational efforts to counter piracy in the Gulf of Guinea.

The region now sees ten times more deaths a year from jihadist terrorism than it did just five or six years ago, a figure which excludes the ongoing Nigerian insurgency. The Gulf of Guinea is now also the epicentre of world piracy, with 130 crew kidnappings in 22 separate incidents. Indeed, the coast of West Africa accounted for 95 percent of global kidnappings in 2020.

Growing Insecurity on Land

The origin of much of the on-land insecurity in the region comes from the 2012 Malian insurgency which initially began as an anti-government revolt in the north of the country. In the initial aftermath of the 2012 Malian insurgency, many of these groups had been contained to the Sahel region or to regions in single countries; however, in recent years they have begun working their way south towards the coast of West Africa through states such as Ghana, Burkina Faso and Cote d’Ivoire. This shift can be seen from that fact that whilst Mali was historically the geographic centre of terror attacks in the region, this has now shifted to Burkina Faso.

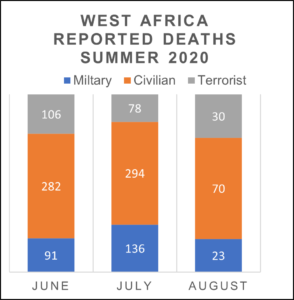

This increase in insecurity and the shift in its geographic epicentre has occurred despite the presence of 5,000 French troops, over 1,000 US servicemen and 15,000 UN peacekeepers on stabilisation missions in the region, of which some are now nearly a decade old. Recent figures for 2020 indicated that between January and October the West Africa region saw 570 terrorist incidents, which directly lead to 2,201 deaths. Further to this, it is also believed that more citizens in the region have been killed by overbearing security forces and government soldiers than have been killed in jihadist attacks.

Now, the region is home to three major and well-trained jihadist groups: the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS); Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), regularly referred to as Boko Haram, and Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), which is linked to al-Qaeda. The United Nations has added that the entire region is on a tipping point and is close to collapse should the situation continue. Indeed, in three countries, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, total combined death tolls from terrorist activity have nearly increased fivefold in four years, from around 750 to 4,000.

The increase in deadly attacks on traditionally perceived secure locations highlights the increasing deadly reach of these groups which originated in the Sahel interior. Mali has seen a number of sophisticated terrorist attacks, including, notably, the 2015 Radisson Blu attack which left 25 dead, and then the 2017 Mali resort attack which left five dead. Cote d’Ivoire saw the 2016 attack at Grand Bassam, and finally, Ouagadougou saw attacks in both 2016 and 2017. In the 2016 attack, two hotels were targeted, leaving 30 dead with 60

injured and 176 hostages who were eventually freed. The 2017 attack also on a city centre hotel resulted in 19 deaths and 25 injuries.

Ghana, so far, has not yet been subject to a large-scale terror attack. However, in the aftermath of the 2016 Cote d’Ivoire attack, it was announced that there was a potential plot to target Ghana, though no attack materialised. Additionally, in the run-up to the national December 2020 general elections, the country’s security officials were aware of the threat that encroaching jihadists could pose. As a result, they increased security levels on the country’s northern borders and politicians issued prominent warnings that the election could produce enough discord that jihadists could take advantage of.

The New Islamic State?

Mali has recently released a large number of Jihadist fighters from prison. Those released are estimated to give ISGS and JNIM an extra 10 percent, potentially more, fighting men. In addition to the extra manpower, it is also believed that those released include veteran fighters, with many experienced tacticians, including those behind the coordinated and sophisticated attacks on hotels in Mali, Cote d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso.

Additionally, alongside the prisoner release, it is believed that Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) received anywhere between 12 and 35 million USD in ransom sums. Such funding enables the group to continue to buy arms and fund its campaigns against various West African governments.

On the whole, the jihadists have been successful in consolidating their hold in the Sahel and are successfully posing a threat to the coastal West African nations. Burkina Faso has been struggling to secure its northern border against jihadist incursion since 2014 and the revolution which led to the toppling of President Compaoré. In Cote d’Ivoire, which over the summer of 2020 declared it had secured its borders with Burkina Faso against jihadist incursion, it only took three weeks for at least 20 insurgents on motorcycles to cross the border and kill 14 soldiers and policemen at the border outpost of Kafolo.

However, it is not just the practical application of violence that has allowed these groups to do so well in recent years. They have also tried to emulate some basic functions of statehood. For instance, ISWAP enforces taxation in the areas it controls, and even uses ISIS created accounting software called Idariya. They have also become more professional and efficient, and no longer use child soldiers or female suicide bombers, realising that communities oppose such tactics. Such reforms are likely a driver for ISWAP achieving a growing share of successful attacks on the region.

Whilst the number and organisational efficiency of the numerous trans-national jihadist groups in the region is largely to blame for the increasing insecurity, the often heavy handed or misguided anti-terror policies of various states in the region are also a contributing factor. Indeed, security forces have often used collective punishments on entire tribal or ethnic groups perceived to harbour extremists or be the cause of the violence. This has resulted in wider and greater resentment within these groups towards the central government and wider state, driving more individuals down the potential path of radicalism.

Alongside this, security forces often, suddenly and without warning, severely curtail individual liberties and freedoms which leads to people being unable to access their work, or markets where they may purchase food from. The inability to access work and food due to severe anti-terror measures helps to foster disenchantment with the central states and, again, leads some down to the path towards radicalism.

There is also the fact that a number of leaders in the region have managed, or are trying, to use the ongoing insecurity in the region as an excuse to push through increasing anti-democratic, or authoritarian, legislation as explored in part one and two of our miniseries. In Nigeria, for example, there is currently an attempt to pass legislation that would allow the authorities to arrest anyone posting content online that could be “taken” to threaten national security.

For extremists, from a financial, ideological and “fame” standpoint, there are also good opportunities to be gained from moving southwards. Coastal West African states contain a number of high-profile targets, both those perceived as western and un-Islamic. Such targets include mining operations, such as Guinea’s lucrative Bauxite mines, which provide 95% of the country’s export earning, or Ghana’s gold mines which provide over 5% of the countries annual GDP and nearly 40% of its total exports, hotels, foreign business, and even western individuals. Cities such as Cotonou and Porto Novo in Benin; Lomé, in Togo; Accra, and Takoradi Ghana and further attacks in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, would all likely be seen as valid targets.

Maritime Insecurity

This growing insecurity should not be a surprise. At sea also, the region has been seeing a slow deterioration for years. The Gulf of Guinea region faces a significant piracy threat, one that local leaders and the international community are failing to address. While areas closer to the coast remain the main focus for these groups, in the past 12 months, their attacks have grown bolder and more likely to target vessels far out to sea, almost with impunity.

With coastal states suffering from a variety of internal problems and often possessing under-resourced and poorly equipped navies, this impacts their ability to efficiently enforce law and order in the gulf. Other problems, which also contribute to insecurity on land, such as high unemployment, weak security, democratic decay, corruption, and the seeming profitability of crime, all also contribute to maritime insecurity.

The best example is Nigeria, the majority of pirate attacks in the Gulf region occur off the country’s coast and are predominantly conducted by Nigerian-based insurgents and criminals and have been for many years without much progress by the country in tackling the issue. This instability and insecurity have also, as discussed in Part 2, coincided with a decline in the country’s democracy. The Nigerian government has sought to demobilise pirate groups with financial incentives in the past, with mixed results. Such instability off the coast has also coincided with an ongoing insurgency in the country’s north, which, despite positive efforts to contain, remains a prominent threat to the country.

Without an effective strategy, such piracy will continue, and coastal communities will suffer, which leads to many of the most vulnerable trapped in a cycle of crime and poverty. For example, at the height of East Africa’s piracy, in 2011 and 2012, there was a 6.5 percent drop in regional tourism, alongside a 23.8 percent regional reduction in fishing exports. The lost income was then coupled with an increased cost in exports and the need to import essential goods, increasing the cost of living. This left communities with a lack of job prospects, apart from turning to piracy.

Conclusion

Going forward, a multi-faceted solution is required for the region. With rising insecurity and democratic decline now feeding off one another, terrorist groups and pirates now have a strong foothold, often with lucrative revenue streams, and this is helping to further increase regional insecurity. Alongside this, instead of looking to effectively combat these hostile actors, leaders are bending the rules and allowing for democratic institutions to collapse. What happens next could have a strong impact on Islamist terrorism, piracy and democracy throughout Africa, and globally.

It can be argued that the presence of regular elections across the region has helped to mask this underlying democratic decline the region has seen. However, the more blatant authoritarian moves made by regional leaders in recent months have brought what was a slow shift into the spotlight. Yet the problems, as illustrated across the mini-series, were always more deep-seated than just elections. Weak democratic institutions never quite lived up to their promise of holding politicians to account, or indeed never lived up to the democratic ideals they themselves declared to follow. Corruption and nepotism have also flourished, and the political class have become detached generationally, and in income levels, from those they claimed to govern for.

Over time this has eroded any trust in the political classes that the regions citizens, and civil societies, had built up. This trust of course is a necessary requisite for a well-functioning democracy. As such, as a symbol of the strong link between democratic decline and instability, a re-assertion of democratic norms in the region

combined with even a reasonably competent provision of state services, would remove some of the more powerful drivers of insecurity in the region.

Terrorist groups have used this lack of democracy, and the accompanying political issues such as lack of investment, to establish themselves in the semi-arid region where effective governance is already a difficult prospect. They have then exploited the widespread poverty, tribal and ethnic tensions and poor security to gain a strong foothold. This has allowed jihadist groups to successfully consolidate their grip in the Sahel and the northern frontiers of West Africa, and are now likely to look to expand, possibly even turning towards other lucrative opportunities in the region, such as the insecurity at sea.

One of the worrying trends in the region is the fact that over the last eight years the insecurity in the region has only grown worse. Despite there being an international intervention in Operation Barkhane led by the French, the insecurity has only increased. Barkhane, which was initially focused on Mali, now sees French troops across much of the region. In early 2021, it was announced the French were looking to reduce their troop presence in the region, and “evolving” the mission. A French exit would be seen as a victory for the extremists and could further erode the credibility of democracy in the region.

Alternatives that could be considered include a new regional multi-national coalition, Western help and training for regional armed forces trying to regain the security initiative against extremists and insurgents. Additionally, and most controversially, opening dialogue and a trust-building process with some of the non-terrorist aligned rebel groups and communities. This will allow for the possibility of a potential compromise on certain political and cultural matters between central governments and those in opposition to it.

As such insecurity puts pressure on governments, alongside usual governance, they have also needed to ensure that budgets are balanced. Chinese loans have become increasingly attractive as they often come with less stringent demands on human rights and transparency when compared to western or IMF loans. This has coincided with, and possibly driven, the political crisis in West Africa.

Despite the challenges that the region faces, there remains hope, that should effective measures be taken by the governments in the region, they can combat at least some of the problems they face. In 2015, combined West African forces launched an effective and successful counterinsurgency operation in Northern Nigeria against Boko Haram, providing a template perhaps for how West African forces can work efficiently together to tackle shared cross border threats of insecurity and terrorism. Additionally, in Niger, despite a violent insurgency, one that has already targeted the elections, the president is stepping down. The country is not alone either, in 2017, Liberia successfully transitioned between presidents after the predecessor, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, stood down after two terms.

This means that western lenders and leaders will be required to play a part in helping to reverse this trend. They could seek to re-engage with the region in the hope that the western advice, and finance with its more stringent demands on governance and transparency could potentially help lead the region towards better governance. This, however, relies on West African governments willing to accept these more stringent western terms, which whilst for some may be acceptable, for those that are already on the cusp of further democratic decline, will likely be something they would rather not have to abide by.

Continue Reading

West African Democracy and Security Part 1: Progress or Regression?

West African Democracy and Security Part 2: The Region Undergoes a Backwards Slide

The Sahel Deterioration and Violence in West Africa in 2024

Examine the recent elections in Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea, emblematic of the broader democratic regressions afflicting the region. These pivotal elections underscore the escalating democratic declines plaguing much of West Africa.

Explore the democratic decline in West Africa, driven by factors like aging leadership, evolving ECOWAS goals, and Beijing’s influence through loans. We also examine Ghana’s position within this context, pondering if it bucks the regional trend or shares in the backward slide.

The Sahel, characterised by growing instability triggered by poverty, food insecurity, water scarcity and challenges presented by terrorism, rebel groups and poor governance, faces threats of further deterioration of security in 2024.