Evacuations from Israel and High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

Sahel Africa – The Evolving French Role

17 Jun 2021

On the eve of the G7 Summit in the United Kingdom, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that France would end all major military operations in West Africa. Despite the announcement, the French army is set to remain in the region for the foreseeable future, with the president already stating that counter-terrorism special forces are likely to continue operations.

Executive Summary

French President Emmanuel Macron announced last week that France would end all major military operations in West Africa. The announcement is likely to be widely supported by the French public and comes as the incumbent president gears up for elections in 2022. However, with frequent jihadist attacks and political insecurity throughout the Sahel, this change in the role of the French military will be uncomfortable for both local leaders and the wider international community.

While French forces are expected to stay in the region in a different capacity, the situation remains volatile. The region is now fast becoming the epicentre for terrorist activity in the world, with recent mass-casualty attacks occurring in a number of countries. The drawback of French troops will almost certainly only serve to embolden the many jihadist groups in the region. Any security vacuum caused by the French military drawdown is highly likely to be exploited and will result in an increase in frequency and, potentially, the severity of Islamist attacks across the region.

The Sahel – Why the Region Matters

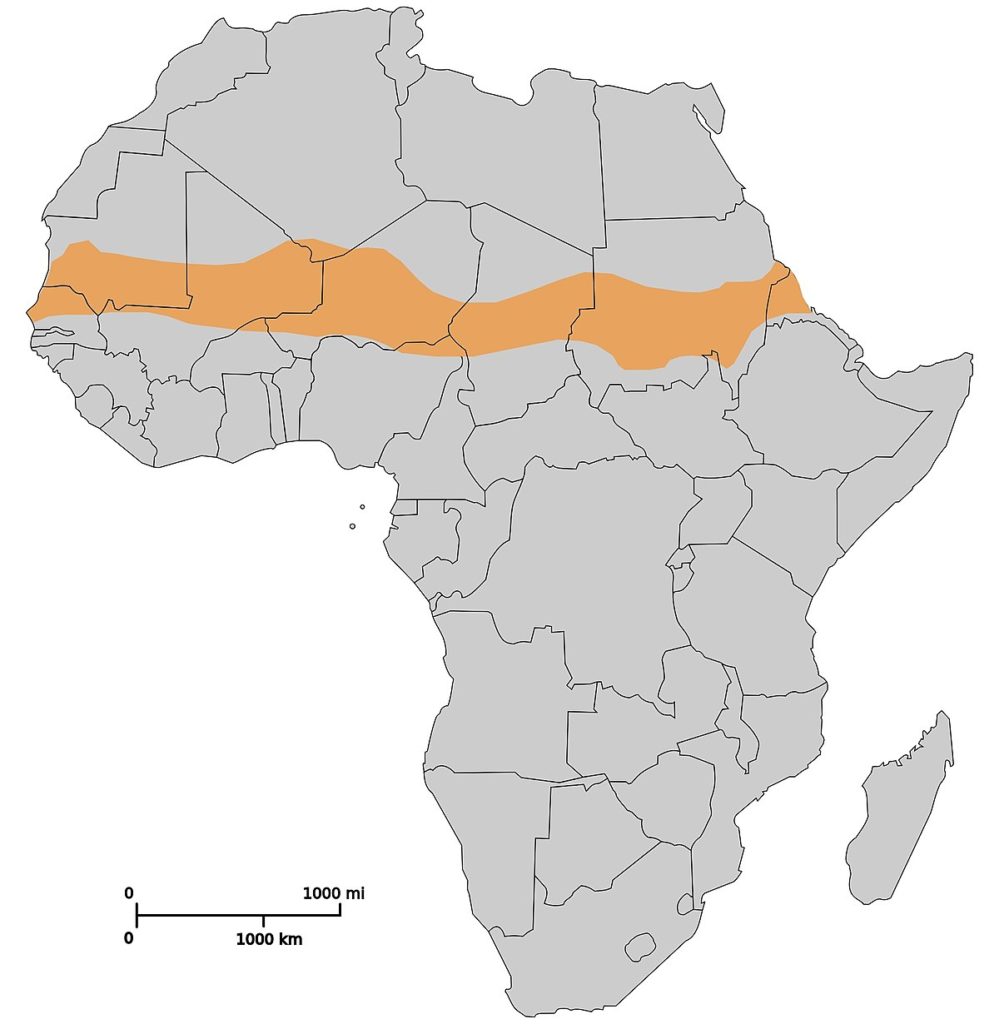

There are many different political definitions regarding which countries belong to the Sahel. There is a core group of the anti-Jihadist G5 Sahel; Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger. However, Senegal, Sudan, South Sudan and even Eritrea and Nigeria are also often included. In purely geographical terms, the region spans Africa from the Atlantic to the Red Sea and is between the Sahara and the varied climates of tropical forests, savannah and mountains to the south.

The region is amongst the poorest in the world and has been beset by conflict, especially ethnic violence, poverty and the extreme effects of climate change for decades. Jihadism has also long been a common theme in the region, with Osama bin Laden using Sudan as a base in the 1990s before moving to Afghanistan. Now, the Islamic State has shifted focus into the region following setbacks in the Middle East, while Boko Haram and groups affiliated to al-Qaeda have also long operated in the almost ungovernable territory. Usually using the aforementioned poverty and ethnic tensions to recruit new members.

Despite these challenges the region faces, it is also a large aquifer and has great potential for both those who live there and the wider African and international communities. The region is one of the richest in the world in terms of natural resources, including oil, gold and uranium. There is also great potential for renewable energy in the region.

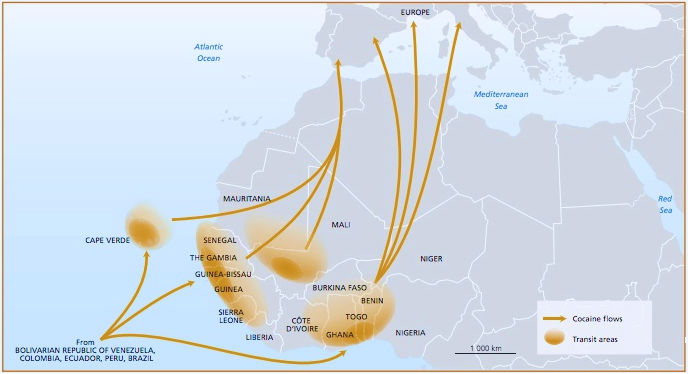

To the wider international community, the Sahel is strategically important for two main reasons. Firstly, it is a transit route for migrants looking to make their way to Europe. Secondly, it is also a major transit route for many of the illegal drugs sold in Europe. Cocaine from Latin America and Heroin from Afghanistan are both heavily smuggled through West Africa as an important stopping point to get the drugs into the European market. In 2009, it was estimated that two-thirds of the cocaine coming from Latin America to Europe passed through West Africa. Some drugs from Latin America to the United States even use West Africa as a transit point, an example being in 2019 when 1,910kg of cocaine were found by police in Guinea-Bissau, with dozens arrested, including Colombians and a Mexican.

The Changing French Involvement

On the eve of the G7 Summit in the United Kingdom, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that France would end all major military operations in West Africa. Despite the announcement, the French army is set to remain in the region for the foreseeable future, with the president already stating that counter-terrorism special forces are likely to continue operations. Macron also stated that France would re-enforce “co-operation” with French troops supporting the Takuba Task Force that is conducting joint operations in the region. This announcement means that Paris is planning to change the role its armed forces play in the region, rather than remove them altogether.

The reasons for this announcement are varied; but centre on two main aspects, the upcoming French elections and weak governance in the Sahel. The French President is set to fight for re-election in 2022 and is already entering campaign mode. The president will be conscious that many in France are doubtful of the French mission in the Sahel. As such, Macron will hope that this “rebranding” of what is, in essence, an unwinnable war, will play well to the domestic audience.

Paris is also not keen on propping up corrupt, undemocratic leaders, regardless of the overall anti-jihadist goal. As discussed in a three-part series earlier this year, the West Africa region, including the Sahel, has seen a democratic backslide in recent years. Macron even added that “France would not stand by a country where there is no democratic legitimacy.” Paris is also at odds with Mali’s plans to negotiate with militants.

As a result, instead of stabilising the situation and seeing the fragile democracies in the region to flourish, French forces have been bogged down fighting an Islamist insurgency, losing 55 soldiers in the process and failing to address the underlying issues, of which there are many. All while military coups and botched elections have taken place. In the past 12 months, there have been three coups in the region, one in Chad and two in Mali. As well as a number of questionable elections, including in Guinea, Niger, Republic of Congo, Benin and Cote d’Ivoire.

These challenges have only served to fuel and contribute to the insecurity in the region. With attacks now commonplace and only eclipsed in frequency by those in Afghanistan. Ultimately, for France, its strategic goals have failed despite a near-decade of fighting.

The Growing Islamist Threat

The main reason for this is, despite the French involvement, in both Mali and the wider Sahel region, since early 2013, the region has become one of the pre-eminent areas for Jihadist insurgencies. In November 2020, the Global Terrorism Index published a report which highlighted that Islamic State (IS) attacks in the sub-Saharan African region were up 67 percent. It added that the “centre of gravity” for IS has now moved away from the Middle East and towards Africa, with the main driver being attacks in the Sahel and a growing insurgency in Mozambique.

Violence has only increased in late 2020 and in 2021. For example, most recently, in June 2021, more than 160 people were killed in a border village in Burkina Faso. This attack followed another that killed 30 people in the village of Kodyel. Additionally, Niger has seen a number of attacks since 1 January, two of which resulted in more than 100 fatalities each, another saw more than 50 fatalities. Governments have also been hard-pressed, Malian, Chadian, Nigerian and Ivorian soldiers have all been killed in ambushes and gunfights. In April, two Spanish journalists were killed, and an Irish citizen abducted.

There are a number of main terror outfits that operate in the region, such as Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, Boko Haram, Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). Support for these groups is changeable with alliances between them being fluid. For example, a dispute within Boko Haram resulted in many fighters leaving and forming ISWAP. On the other hand, elsewhere, ISGS and Jama’at Nasr militants are currently allied and regularly link up to resupply and support each other.

The support, recruitment and supply for these groups come from a number of sources. Firstly, the region is desperately poor, and locals have next to no hope for improvement from the governments in the region. There are also underlying ethnic tensions, allowing terrorist groups to recruit individuals who already have a deep mistrust of their neighbours. Additionally, the collapse of Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya has deprived the region’s north of a stable bulwark against militants and jihadists. The resulting civil war in Libya also allowed the mass recruitment of jihadists. Finally, the defeat of the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria saw many of their soldiers flee to Africa.

These groups are also well funded. In addition to the drug routes in the region, there is the ability to trade illegal wildlife. Kidnap and ransom payments also provide such groups with another highly profitable revenue stream. Such payments are contentious and have caused tensions among western allies. Notably, an agreement by the G7 in 2013 not to pay ransoms to proscribed terrorist organisations has not been followed by all countries, such as France. As it stands, European citizens tend to be eventually released for undisclosed amounts, whereas American and British hostages are the most likely to get executed. Indeed, several French citizens have been released from jihadist captivity in the Sahel region, with a recent exchange involving a large number of jihadist prisoners in Mali.

This threat extends beyond the Sahel. There have been attacks in Tunisia targeting soldiers on the country’s border with Algeria. In Algeria itself, five people were killed following an IED explosion in Telidjane District. Also in Algeria, this time in Tipaza Province, two soldiers and four militants were killed in an exchange of gunfire.

What Next? – In Need of a Coalition

Given the jihadist threat and other insecurity concerns, France and other international partners cannot simply withdraw their military support. Macron has already announced that special forces contingents will remain deployed. He added that those left in the region will work with other European nations fighting alongside Mali, Nigeria and others. Whether this will be enough remains unclear. The jihadists are well entrenched, and it remains highly unlikely that the region’s issues will be solved in the coming decades.

While Macron’s decision will give the president a domestic boost, it is likely to be viewed, in the longer term, as a negative for the region and internationally. Paris had been looking for European allies and the United States to join them in providing combat troops to the region. London and Washington, who are already war-weary from decades in the Middle East, are unlikely to invest in another prolonged conflict if Paris is looking to scale back their own involvement.

Military leaders in Mali and Chad have also, vaguely, promised elections following their coups. These coups had received much backlash among countries in the region, as well as from France and other western powers. However, with France scaling back their involvement, military officials are less likely to relinquish power. The African Union may also be less inclined to punish them, especially given how vital Chad’s military is to the region.

The change in policy also does not reflect the situation on the ground. The recent attacks should serve as a warning to the region, Europe and the global community to combat the threat. As seen in Algeria and Tunisia, insecurity in the Sahel can result in insecurity in neighbouring countries. Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, as well as Libya, could all face a growing Islamist threat should the Sahel be left unchecked. Nations along the Gulf of Guinea coast are also at risk of insecurity, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana and Senegal could all see the security situations in their countries deteriorate.

Of course, the solution does not rely solely on military operations, however. Stable governance, and the quality of it, are vital. As was seen in Iraq and Afghanistan, a significantly stronger, well-armed and focussed Western intervention will only be able to do so much. For such counter-insurgency operations to succeed, local governments and forces need to be competent, the local population need to be won over and economic opportunity has to be provided.

Sheer military determination will not bring a lasting victory. Instead, local and international economic investment that would begin to give locals options beyond a life of violence is needed. However, to achieve this, France and other western allies will be required to invest a huge amount of resources to make any sort of impact.