Evacuations from High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

Turkish Operation Peace Spring: A New Syrian Frontline?

18 Oct 2019

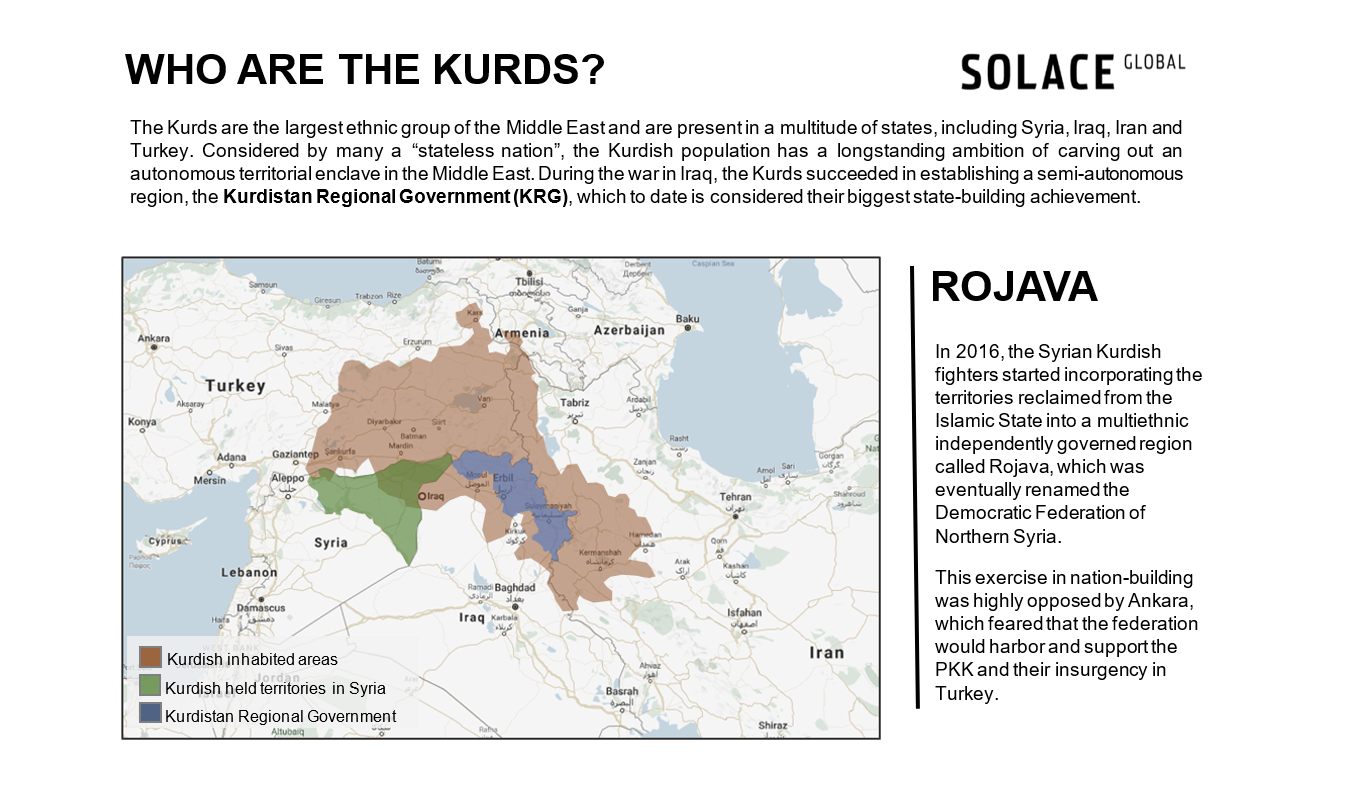

On 10 October, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan officially initiated an offensive military campaign, Operation Peace Spring, in northern Syria, with the declared objective of creating a safe zone in the Kurdish-held territories along its southern border. The offensive started shortly after the sudden and controversial withdrawal of the US troops stationed alongside their Kurdish allies, seemingly to accommodate the Turkish plan.

Key Points

- On 10 October, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan officially initiated an offensive military campaign, Operation Peace Spring, in northern Syria, with the declared objective of creating a safe zone in the Kurdish-held territories along its southern border.

- The offensive started shortly after the sudden and controversial withdrawal of the US troops stationed alongside their Kurdish allies, seemingly to accommodate the Turkish plan.

- To respond to the Turkish aggression in the absence of any American military support, the Syrian Democratic Force (SDF) reached a landmark agreement with Bashar al Assad in Damascus. The governmental forces have moved along the provisional frontline and key cities, sparking fear of another conflict emerging in Syria.

- The international community has widely condemned the Turkish offensive and has expressed concerns over the possibility of ISIL and other insurgent elements taking advantage of the growing instability to regroup and rearm, fundamentally compromising the counterterrorism efforts of the past five years.

The Military offensive

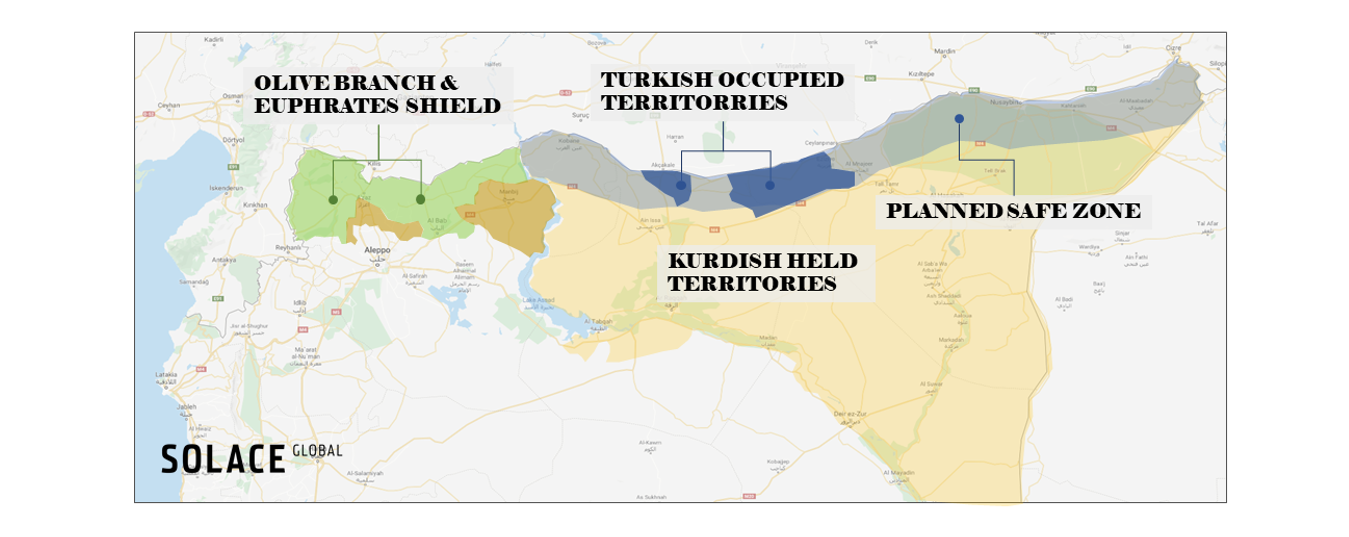

On 9 October, the Turkish Armed Forces launched a ground and air assault against the Syrian Democratic Force (SDF), stationed in the semi-autonomous occupied territories in north-eastern Syria. The objective of the offensive is to create a “Safe Zone” in the Kurdish-governed territories, where Erdogan plans to reintegrate part of the thousands of Syrian refugees currently hosted by Turkey. Additionally, the presence of the SDF along its borders, which Ankara deems a violent insurgent force, represents a critical national security issue and Erdogan has detailed his plans to secure a buffer zone in several occasions and fora, including the UN.

Both the timing and the general context of the military operation have been criticised by the international community, due to it taking place shortly after a partial withdrawal of American troops stationed along the border, which had been conducting joint patrols and stabilisation operations with the Kurdish forces. The Syrian Democratic Force has been a US ally since around 2016, when it independently initiated a large-scale counterterrorism campaign that culminated with the liberation of Raqqa, the de facto Syrian capital of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Armed and supported by Washington, the SDF played a central role in the eradication of Islamic terrorism in north-eastern Syria, where the Kurdish leadership established a semi-autonomous, democratically governed enclave under the leadership of the Democratic Union Party (PYD).

On the other hand, Turkey, a NATO member, had repeatedly equated the Kurdish militia to the PKK, or Kurdish Workers Party, a violent insurgent group active in the region, especially Turkey, since the 1980s. For over three years, Erdogan has expressed his grave concerns over the consolidation of an autonomous Kurdish region, with whom Turkey shares a 300km long border, and which he accused of being just a front for the PKK.

Now that the US has declared victory over the ISIL in Syria, the cohesion of Washington’s regional alliances and its commitment to the conflict have suffered significantly, as evidenced by President Trump’s repeated attempts to withdraw American troops and disengage from the civil war. The 9 October withdrawal has, however, strategic consequences that go beyond an attempt to localise the conflict, as allowing the immediate Turkish advance specifically targeting Kurdish forces was widely perceived as a betrayal and the prioritisation of one alliance over another.

Moreover, the subsequent decision of the SDF and the Democratic Union Party to strike a deal with the Syrian government in Damascus, which allows their forces to enter Kurdish-controlled territories to jointly retaliate against Ankara’s offensive, represents a radical shift that was previously considered unthinkable and will likely result in a prolonged standoff and further instability in the region.

Why is Turkey attacking Syria?

Ankara’s latest military campaign represents an unprecedented intervention in Syria, but it is far from being its first. In the past four years, Turkey has pursued what has officially been deemed a counterterrorism campaign. This, through the 2016 Operation Euphrates Shield and the 2018 Operations Olive Branch, effectively led to the establishment of different areas of control in the country’s north-west. While the context of the campaigns was counterterrorism and border security, two of Turkey’s primary national security priorities, they resulted in several clashes with the Kurdish forces in the region and, ultimately, the seizure of Afrin, one of their key territorial enclaves.

The current hostilities, taking place between two factions formally allied to, and supported by, the United States, have been partially justified by Erdogan as an offensive targeted specifically the YPG, which he considers an insurgent group due to their association to the Kurdistan Worker Party (PKK), a secessionist militia active in Turkey and listed as a terrorist organisation by both the US and NATO.

The US President has addressed the latest military offensive by defining the Turkish and the Kurds as “natural enemies”, but whether the PKK can be simply equated to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the multi-ethnic militia of the Kurdish-controlled territories, remains contested. According to Ankara, the PKK’s seasoned fighters have played a pivotal role in shaping and training the SDF personnel, aided by the highly decentralised governmental structure of the Kurdish enclave.

Moreover, Erdogan has repeatedly expressed concerns that an autonomous or semi-autonomous Kurdish region will harbour and support the PKK’s subversive agenda in Turkey, fear only heightened by its proximity with the country’s southern border.

Overall, almost all the Middle Eastern nations housing a relevant Kurdish minority have historically shared strong anti-secessionist sentiments. This has led them to occasionally cooperate, despite their sometimes-confrontational bilateral relations, due to what they considered an overarching security threat. Syria, for instance, excluded the Kurds from its political opposition since 2011 in response to a request from Turkey, as a result of their role in legitimising the PKK as a political stakeholder rather than an insurgent group.

However, since 2015, when the latest round of peace talks between Erdogan and the PKK collapsed, Turkey’s hostility against the Syrian Kurdish population escalated significantly and was further amplified by their rapidly expanding territorial enclave along the border. The success of the SDF in fighting the ISIL caliphate in Syria, which granted them American military support, weaponry and training, further angered Erdogan, who feared that that would legitimise the sovereignty of the Kurdish authorities over the north-eastern Syrian territories.

The Damascus agreement

On Sunday 14 October, only five days after the start of Operation Peace Spring, the Kurdish forces announced a landmark agreement with the Syrian government in Damascus, which allows them to deploy along the Turkish border to provide much needed assistance in the efforts to retaliate against Ankara’s offensive. Moreover, their cooperation will extend to all territories currently held by Turkish forces, including the former Kurdish enclave of Afrin, which was occupied during the 2018 Operation Olive Branch.

The agreement, brokered by Moscow, represents a dramatic shift away from the strategic status quo and, therefore, the alliance with Washington. The decision was most likely motivated by the relatively weak reaction of the US, previously a key Kurdish military partner, to Ankara’s successful and rapidly expanding military campaign in Kurdish territories. On the other hand, Washington had announced on Sunday its intention to further withdraw from northern Syria in response to Turkey’s decision to widen its operation southwards.

While Washington has vehemently denied all allegations of having endorsed or greenlighted Ankara’s offensive campaign, highlighting its intention to retaliate with the imposition of economic sanctions, Trump’s desire to pursue military disengagement despite its humanitarian and strategic costs seems increasingly certain. The US has never made a secret of its goal to disengage from the costly commitments to wars in the Middle East and President

Trump had already announced in December 2018 his intention to withdraw 2,000 US troops from Syria, later halving the number due to strategic considerations. It is the lack of the same strategic disposition, which would advise against the sudden creation of a power vacuum in a contested territory that might have led the Kurdish leadership to reach out to the opposing faction despite the intrinsic risks.

Trump had already announced in December 2018 his intention to withdraw 2,000 US troops from Syria, later halving the number due to strategic considerations. It is the lack of the same strategic disposition, which would advise against the sudden creation of a power vacuum in a contested territory that might have led the Kurdish leadership to reach out to the opposing faction despite the intrinsic risks.

The Syrian governmental forces have now reached the frontline along the northern Syrian M4 motorway and central regional supply line, as well as several key towns in Kurdish-held territory, preparing to retaliate against Turkish aggression and re-establish sovereignty over their border.

Uncertainty, however, remains over the future of these territories when “liberated” by this newly formed partnership and whether the Kurdish population would have any right to claim ownership or even control over its previously autonomous enclave. For years the Syrian governmental forces have been shut out form this region, partially as a result of the US military presence, which allowed the Kurds to attempt a democratic state-building exercise, which certainly did not go unnoticed by Bashar al-Assad.

Will the “Safe Zone” be actually safe?

The sudden withdrawal of US troops from northern Syria has had great strategic repercussion on the regional dynamics, highlighting the risks of an erratic foreign policy in complex conflict areas. Faced with the unexpected loss of American support and a military offensive by a hostile neighbour, the Syrian Kurds had very little choice than to turn towards Damascus for aid. The agreement, brokered by Moscow, highlights the primary strategic formula in the region, where to an American withdrawal or loss of leverage in the Middle East almost immediately equates to a strengthening of the Russian and sometimes Iranian influence.

Through his intervention in the Kurdish territories, Bashar al-Assad has regained access to an area of the country that was increasingly becoming autonomous, which also increases the credibility of his sovereignty claims over the Syrian territory.

Turkey’s aggressive posture has also produced significant fractures among NATO allies and regional stakeholders, notably the European Union. The retaliatory economic sanctions imposed by Washington, which are far from matching those in place against Iran, have been disregarded by Erdogan and are widely considered of marginal impact to the Turkish economy.

The EU member states have, instead, adopted a tougher stance, pledging to suspend weapon sales to Ankara, coupled with unilateral embargos initiated by countries such as Finland, France, Germany, Sweden and the UK. Further measures are likely to follow if the offensive by Turkey, once an aspiring member to the European Union, continues, particularly in the aftermath of Erdogan’s threat of unleashing waves of unregulated refugees towards European soil if any of its states openly criticised the military offensive.

The Turkish military campaign in northern Syria has, however, sparked fears in the regional and international stakeholders that goes beyond the emergence of another frontline in the ongoing conflict. While the chances of full-scale warfare between Syria and Turkey are slim, particularly as Russia has been playing a buffer role by conducting patrols between the two forces, it is also unlikely for the standoff to be rapidly resolved.

Together with the simple acknowledgement of increased levels of localised violence leading to instability, several officials have expressed concerns regarding the risk caused by significant portions of the available security and military resources held by the Kurds and the Syrian government being redirected north towards the new frontline, notably away from Raqqa.

This will decrease the ability to effectively monitor and secure large portions of the Syrian territory, allowing for dormant terrorist cells, as well generally radicalised individuals, to take advantage of the growing instability to regroup and conduct disruptive campaigns. These concerns were only heightened by the two terror attacks in Qamishli and the US base in Shadadi that took place right after the beginning of Turkey’s offensive. Moreover, instances of several dozens of IS prisoners previously held in Kurdish prisons have already escaped, thanks to the infrastructure being damaged during the shelling.