Evacuations from Israel and High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

Hurricane Barry Spares New Orleans: Adverse Weather Continues

15 Jul 2019

Hurricane Barry made landfall in Louisiana on 14 July, quickly weakening to a tropical storm. While the city of New Orleans was for the most part spared, other towns up the Mississippi River have experienced flooding, power blackouts and disruptions. Louisiana governor announced a state of emergency across the state due to the ongoing threat of heavy rains. Mandatory evacuation orders and flood warnings were issued across the state. Barry triggered flooding and disruption across the state; though no injuries were reported.

Key Points

- The low-pressure system over the Gulf of Mexico, reached hurricane strength as it neared Louisiana’s coast but was downgraded to a storm after making landfall.

- Louisiana’s governor announced a state of emergency across the state due to the ongoing threat of heavy rains. Mandatory evacuation orders and flood warnings were issued across the state. Barry triggered flooding and disruption across the state; though no injuries were reported.

- Tropical Strom Barry could have had a worse impact as the Mississippi River contained unprecedented water levels. New Orleans’ flood systems would have been tested since the deadly failure of the flood protection measures during Hurricane Katrina (2005).

SITUATION SUMMARY

On 13 July meteorological sources confirmed that Tropical Storm Barry, the low-pressure system over the Gulf of Mexico, strengthened to a Category 1 hurricane. At that time, it was expected to bring hurricane-force winds, storm surge, up to 38 cm of rainfall and subsequent flooding to parts of Louisiana, Notably to an area west of New Orleans. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) warned that Barry possessed maximum sustained winds of 120 km/h (75mph) moving toward the southern coastline of Louisiana at nine km/h.

Ahead of the anticipated landfall, Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards announced a state of emergency. President Donald Trump also declared a federal emergency in Louisiana; the Department of Homeland Security and Federal Emergency Management Agency were then authorised to coordinate the relief efforts ahead of a possible emergency. Severe rainfall and consequent flooding, particularly near rivers, were anticipated together with damage to properties and infrastructure, road closures and travel-related disruptions. Parts of Louisiana were forecasted to be severely affected, therefore, evacuation orders were issued; this included the town of Grand Isle, and Jefferson, Plaquemines, Lafourche, and St. Charles parishes.

In addition to this, a storm surge warning was in effect for areas from Intracoastal City to Biloxi (Mississippi state) and for Lake Pontchartrain. The National Weather Service issued a flash flood emergency for New Orleans and nearby areas as, the already-swollen Mississippi River, was forecasted to peak above flood stage. New Orleans mayor LaToya Cantrell advised residents to prepare for heavy rain and wind and to take shelter. Airport operations were also suspended at New Orleans’ Louis Armstrong International Airport. In New Orleans, the flood threat was a fresh reminder of Hurricane Katrina’s deadly storm surge that killed thousands of people in 2005.

During afternoon hours local time on 13 July, the storm that reached hurricane strength as it neared land, weakened to a storm with sustained wind speeds of 96km/h; it mostly spared the city of New Orleans from a potentially devastating landfall. Weakened but still a threat, the system triggered a sea surge in Mandeville and broke a main river levee in Plaquemines Parish. Hundreds of people were also evacuated in Terrebonne Parish where the United States Coast Guard helicopters were also deployed to assist local authorities with relief operations.

In Baton Rouge, strong winds reportedly damaged properties and downed power lines. Across Alabama, flooding triggered road closures, and local reports from emergency management agencies suggest that heavy rains and flooding contributed to a high number of accidents. On 14 July, updated reports indicated that thousands of people were without access to power and more than 11 million residents from the cost of Louisiana to the southern Midwest were still under flood warnings.

At the time of writing, meteorological authorities reported that Tropical Depression Barry is forecast to move north-northeast and northeast and is anticipated to dump a further rainfall in already inundated areas of Louisiana and Arkansas.

SOLACE GLOBAL COMMENT

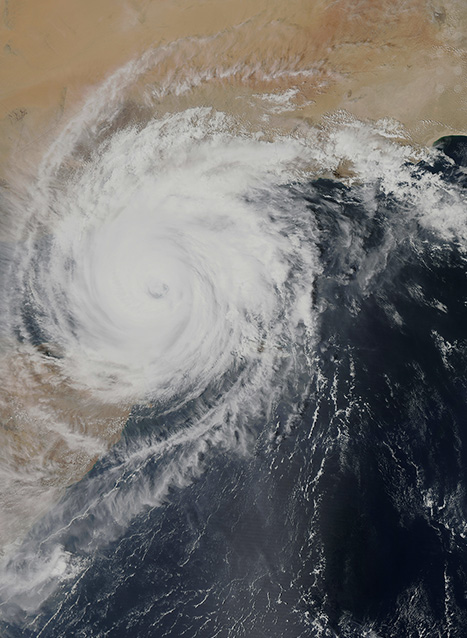

On 12 July, images from the satellite of the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration captured Barry enveloping most of the Gulf of Mexico as it tracked towards the Louisiana coast. At that time, the National Weather Service predicted that Tropical Storm Barry was likely to become a hurricane. Furthermore, since the system was “slow moving”, there was an increased threat of more rain and larger floods compared to a faster system.

Barry’s impact at landfall was also predicted to be compounded by the water levels of the Mississippi River being already higher than normal. Moreover, while most of the levees on the Mississippi have been upgraded in the aftermath of the deadly Hurricane Katrina, the entire network of secondary rivers, lakes and canals in the region also suffers from the same heavy water risk. The fear of flooding was particularly strong in the vicinity to New Orleans, a low-lying area on the banks of the Mississippi River that is deemed America’s most vulnerable to hurricanes by the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Its topography makes it susceptible to sea surges and heavy rainfall, as well as inundations from the Mississippi River when not successfully contained by its levees.

With the memory of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation still fresh in the city’s minds, concerns about Barry’s flood risks were high, particularly regarding the river levees, as in 2005 more than 1,883 people died due to the failure of New Orleans’ canals flood system. Up to 80 percent of the city was inundated in what was described as the deadliest disaster in the history of the United States. For this reason, New Orleans authorities had resorted to emergency preparedness initiatives, such as pre-positioned boats and high-water vehicles across the city, as well as city-wide deployment of the National Guard. While the evacuation was deemed unnecessary at that stage, the city’s mayor requested the residents to remain sheltered in their homes.

Thankfully the fears that Barry may impact New Orleans like Hurricane Katrina did in 2005 were unfounded. Authorities reported that they did not expect the Mississippi River to rise over the levees and while some damage and flooding has been reported, it has been far less than first feared. However, with Barry moving through northern Louisiana into Arkansas, rainfall continues to be the storm’s biggest threat, and, as a result, flooding could still cause life-threatening conditions in some areas. Authorities are urging residents to stay alert and follow all of the warning and instructions from officials.

SECURITY ADVICE

EnvironmentModerateThe Atlantic hurricane season began on 1 June and will end on 30 November. In specific, the peak event frequency is from mid-August to mid-October; while June and November see fairly rare storm formations. Travelling during the hurricane season to hurricane-prone destinations poses a number of risks. By following critical security measures and advice, their impact on your travel and safety can be mitigated:

However, should you have to travel, be caught unexpectedly or live in the path of a storm, it is important to: