Evacuations from High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

Lebanon: Another Arab Spring or a Path to Chaos?

3 Dec 2019

Lebanon has been experiencing over six weeks of civil unrest, taking place in several cities including Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon and Tyre. This wave of civil unrest is unprecedented in scale and type, as it successfully bridged sectarian divides in favour of a comprehensive socio-economic movement.The demonstrators, representing all the several religious minorities in the country, are demanding political change and some even a complete overhaul of the current political structure, which is being accused of fostering corruption and clientelism.

Update 27 Sept 2024: See further information on the developing situation in Lebanon

Key Points

- Lebanon has been experiencing over six weeks of civil unrest, taking place in several cities including Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon and Tyre. This wave of civil unrest is unprecedented in scale and type, as it successfully bridged sectarian divides in favour of a comprehensive socio-economic movement.

- The demonstrators, representing all the several religious minorities in the country, are demanding political change and some even a complete overhaul of the current political structure, which is being accused of fostering corruption and clientelism.

- Hezbollah, successfully integrated into the government since 2005, has been taking to the street to counter the protests, which resulted in a number of violent clashes. The armed forces have been acting as a buffer between Hezbollah affiliates and the anti-government demonstrators, but an escalation in violence is likely to require a stronger response by the military, sparking fears of a new civil conflict.

- While the highly structured political system has been credited as the key enabler of democracy and civil liberties, as well as for being a moderator of extremist groups, it has also allowed the corruption levels to grow uncontrolled and resulted in a stagnant economy rooted in mismanagement and political obstructionism.

- Resolving the current political standstill is, however, absolutely necessary to implement the economic and financial reforms that would prevent the country from defaulting

The Crisis

On 26 November, after over a month of violent protests, interim Prime Minister Saad Hariri announced that he will not seek to lead the next government, hoping to expedite the cabinet formation after his resignation. Leader of the March 14 Alliance and son of Rafic Hariri, former Prime Minister who was assassinated in 2005, Saad Hariri was expected to lead the government possibly for decades, as his family has almost continuously held power since 1992.

He was, however, forced out of his post on 29 October, after he was blamed by the demonstrators as one of the figureheads of a corrupt political elite that the demonstrators want out of the Lebanese governing structure. While his decision to not pursue power further, coupled with the introduction of “unprecedented economic reforms”, demonstrates a degree of responsiveness from the government, it is unlikely to quell the ongoing demonstrations.

The reform package, introducing privatisation measures, salary cuts for government officials, and an anti-corruption commission, as well the change in leadership in one of the political dynasties, is far from representing a significant change in policy, an improvement of public services or a solution to the political standstill.

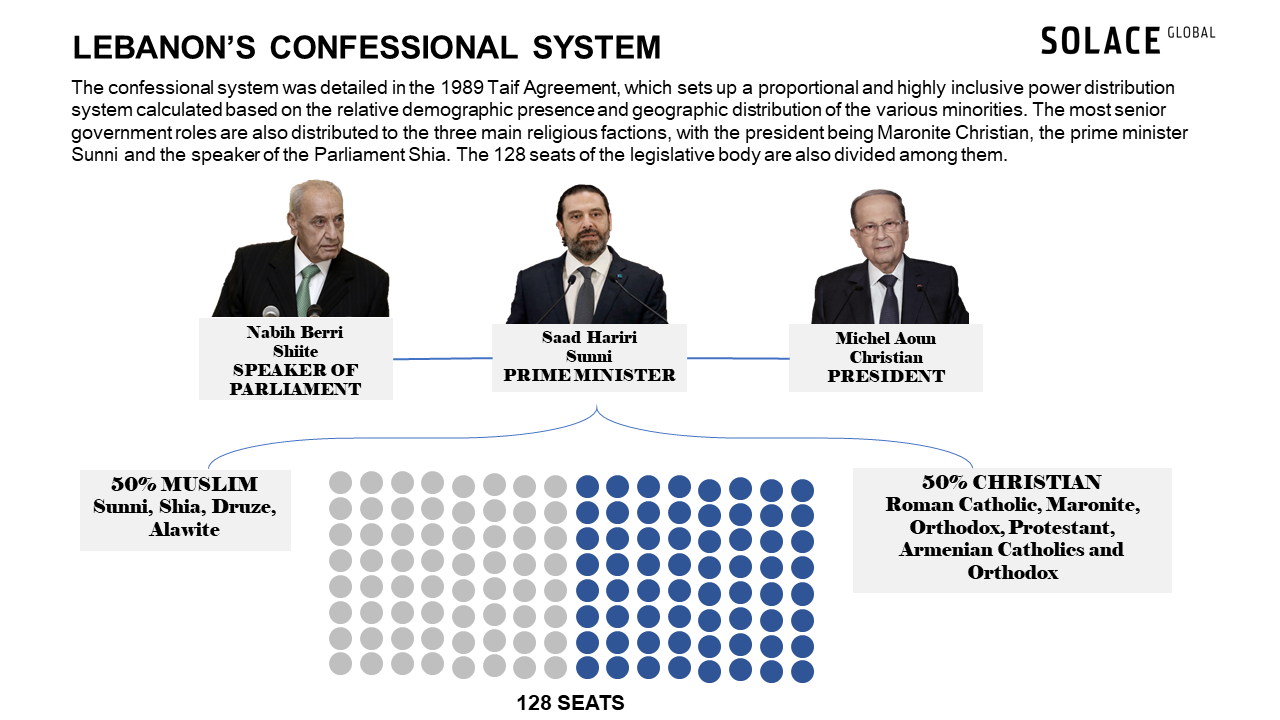

The protesters are now increasingly demanding a radical political change, some of the leadership of all the main sectarian political entities, or in more extreme cases of the entire confessional system. The system, built on a principle of proportional power-sharing among the three main religious majorities in Lebanon, represents a key issue to understand the political causes of the economic stagnation and what makes this wave of civil unrest unprecedented.

The protesters are now increasingly demanding a radical political change. While most are calling for a change in the leadership of the main sectarian political entities, others have suggested the elimination of the entire confessional system. The system, built on a principle of proportional power-sharing among the three main religious groups in Lebanon, largely represents one the key political causes of the economic stagnation and was instrumental in allowing this wave of unrest to transcend the traditional sectarian divides for the first time.

The Spark and the Root Causes

The current Lebanese crisis is not, however, only socio-political, but inherently tied to a failing economy, financial mismanagement practices, and the rebuttal against a corrupt political elite. On 17 October, the demonstrators took to the streets to condemn a bill that introduced a new tax on internet-enabled calls, namely through the popular messaging and Voice over IP service, WhatsApp.

With the costs of traditional calls being unaffordable for a vast majority of the population, the initiative angered thousands of citizens, which condemned the tax as another attempt by the government to quickly gather financial assets at the expense of the population, rather than addressing the inefficiencies that led to the crisis in the first place.

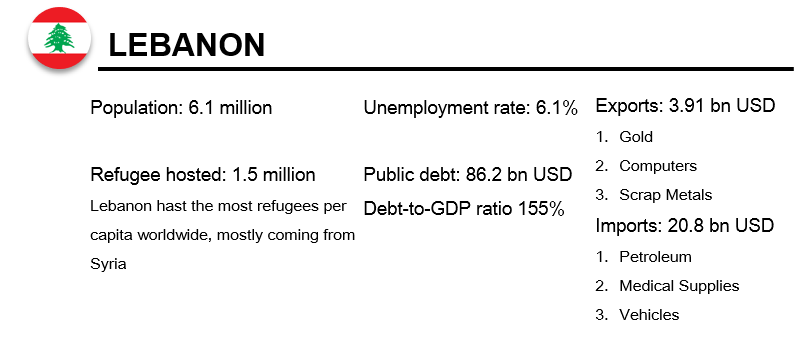

With a debt-to-GDP ratio of 155 percent, Lebanon is the third largest indebted country in the world. For decades, its economy has fundamentally relied on a currency pegged to the USD, coupled with high levels of remittances from the Lebanese diaspora and deposits from the Gulf countries, to provide for the government’s activities while maintaining the current standards of living. While the incredibly high interest rates make remittances very profitable for foreign investors, they also continue to increase the national deficit, unsustainable for a country greatly reliant on imports.

In September, over a month before the start of the protests, the government announced its intention to declare a state of economic emergency and initiate a set of radical reforms to solve the failing economic system. This probably represented the turning point for both the government and the population, with the latter hoping for an actual transition towards a sustainable economic system during the announced six-month window.

The government instead decided to resort to a tactic it frequently relied upon for a rapid fix, using indirect taxation to compensate for its financial and economic shortcomings. The anger that erupted after the latest round of taxes is fundamentally in retaliation to a political elite attempting again to buy time at the expense of its population, while unable to provide a permanent solution for the economic crisis.

However, the political instability throughout the country had the additional effect of causing the currency peg to the USD to start slipping, meaning that, while the banks formally maintain the fixed exchange rates, there is an increasing shortage of USD in the country. For an economy where much of the basic commodities are imported, this has begun to fuel inflation. With petrol, medical supplies and food being amongst the key areas hit by the higher import rates, a sudden shortage has a high potential to paralyse the country completely, bring it closer to defaulting.

Transcending Sectarianism

A largely unprecedented element in this wave of unrest is, however, the cohesive message and action of the different religious minorities, who are actively protesting against their own political-religious leadership together with the government as a whole in order to produce change. The gravity of their economic concerns, affecting a country where an estimated one-third of the population lives in poverty regardless of their religious affiliation, has played a central role in bringing the different factions together.

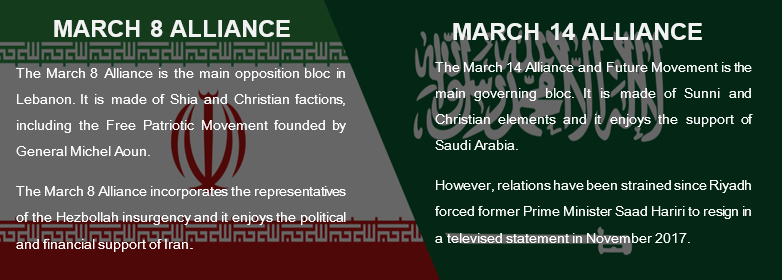

Together with the movement actively asking for a reform of the leadership and the confessional system, this indicates that the Lebanese people are in the process of overcoming the “us versus them” narrative that has been exploited by the different political blocs for decades. The main government blocs, the March 8 and March 14 Alliances, have actively tried to prevent any economic success to be attributed to the opposing faction, often blaming each other for all the country’s inefficiencies. In the meantime, corruption is rampant, the quality and efficiency of public services is deteriorating, while public debt keeps growing.

The members of these religious communities rely on their leadership for almost all aspects of their lives, including the provision of alternative public services, school and hospital fees when the central government fails to, particularly outside the capital city. This has largely contributed to the reticence of the various communities to blame their own leadership, rather than adhering to the “zero-sum-game” narrative common in politics.

Recognising that a political system in which the power distribution cannot virtually change and favours corruption and clientelism, the population is now increasingly demanding a radical overhaul of confessional politics, hoping that this will solve the political obstructionism by the various blocks.

This effort is complicated by a variety of elements: chief among them, the confessional system, which is both the main reason for the government’s inefficiency and the key in mitigating the volatility of such a heterogeneous society and an insurgent militia. Earning Lebanon the title of the only pluralistic and stable democracy of the Middle East, the confessional system was also largely credited for the progressiveness of the nation, a degree of freedom and civil rights generally uncommon in the region.

Elements of Volatility

The presence of Hezbollah in the Lebanese societal and political spheres severely complicates any attempt to change the country’s power sharing structure. On 23 November, supporters of Amal and Hezbollah attacked the anti-government protesters in Beirut, reportedly to deter them from disrupting the capital’s business functions with strikes and road blockades.

The security forces were deployed to form a buffer between the two, but remained wary of directly confronting Hezbollah supporters, in fear of violent retaliation from the group. A violent campaign by Hezbollah has the potential to trigger another civil war, only a few decades after the end of a 15-year-long one. On the other hand, the group has successfully achieved a political presence in the government’s cabinet, which its leadership is unlikely to give up soon.

The group’s affiliation with Iran inevitably emphasises the international and geopolitical context in which this attempt to reform Lebanon’s political system is taking place. Hezbollah, classified as a terrorist organisation by the United States and largely reliant on Tehran for support, has already accused Washington of covertly orchestrating the civil unrest and of general obstructionism to the cabinet formation process.

If the international support system of the two main political blocs is understood to as another, albeit smaller in scale, Middle Eastern proxy confrontation between the Saudi and Iranian powers, then it’s important to take into consideration the overall balance of power in the region.

As Tehran loses support in Iraq, where violent demonstrations have explicitly called for the removal of all Iranian influence in the country and its politics, coupled with its own episodes of unrest, it is logical for the Iranian leadership to attempt to retain relevance in Lebanon in order maintain a semblance of the overall balance of power in the region. On the other hand, it is becoming increasingly difficult for Iran to provide for its own regional proxies, particularly as international sanctions are slashing its revenue sources and domestic instability is mounting.

Moving Forwards

This wave of demonstrations is without a doubt unprecedented for several reasons; the signs of an all-encompassing societal movement that transcends sectarian divides and increasing understanding of how the country’s issues have been used by the different political blocks for their own profit. In this sense, each community is attempting to introduce a degree of accountability for its leadership.

However, its success is far from certain, particularly in the wake of the clashes with the Hezbollah. While these have been smaller in scale, causing only a limited number of injuries, they have the potential, as well as the historical precedent, to escalate into something more dangerous. The military, which has, thus far, acted as a neutral force, will find itself in a conundrum if the violence intensifies, where a face-off between sectarian communities could lead to its internal fragmentation and possibly the formation of smaller militias supporting different sides. The fact that the Lebanese security apparatus receives support from Washington further contributes to Hezbollah antagonistic narrative.

A sudden spike in violence has the potential to either fatally damage or fuel the momentum of the demonstrations but will also force the US-trained Lebanese security forces to intervene rather than act as a buffer, further escalating hostilities. In turn, this could fragment the military itself between those supporting and opposing the different factions, bringing the country closer to a civil conflict. In order to have a credible chance to save the economy, however, the interim government needs to prevent this scenario, as the current instability has already harmed investor confidence and the country’s business activities, while also creating shortages in basic goods.

The situation suggests that foreign intervention, particularly in the form of a large scale bail out in exchange for a process of closely managed change, is likely to be necessary to put a halt to the crisis. With the EU having already expressed reluctance towards granting another loan to Beirut, the intervention is likely to come from Washington, which will put it at odds with the Hezbollah block. Keeping the group largely involved in defining change will most likely be essential to produce any change whilst also minimising violence, but what this change actually entails is still largely unclear. The success of the political change is largely dependent on the actions of Hezbollah in the upcoming weeks, as the insurgent group remains key in enabling or obstructing any institutional or socio-economic shifts in Lebanon.