Evacuations from High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

The Iran Deal: why is it collapsing and what comes next?

11 Jul 2019

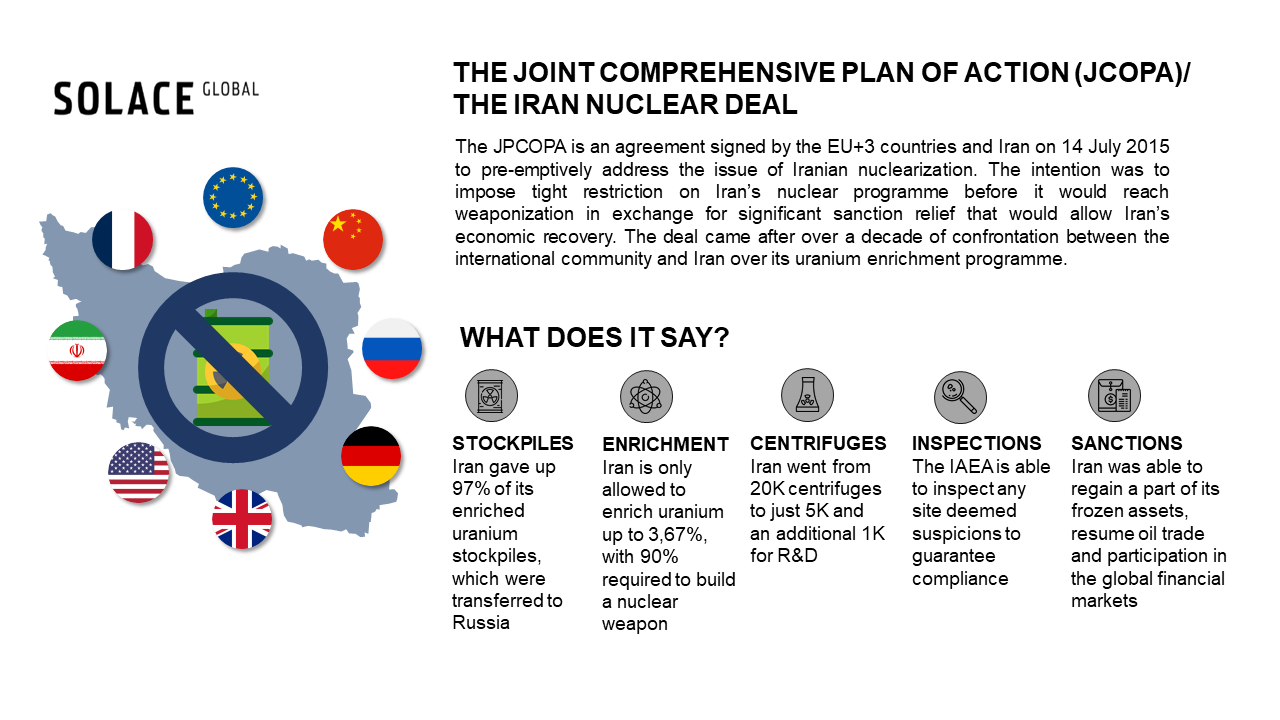

Iran has officially started scaling back its commitment to the JCOPA. The changes, although minimal, represent a retaliation to the mounting US imposed sanctions, which have established an oil embargo against Iran. With the rationale of the deal being stringent restrictions and control over nuclearisation in exchange for the lifting of sanctions, it is unlikely to survive in the absence of a solution for the great loss of revenue for Iran. While direct nuclear escalation is unlikely, the collapse of the deal will result in low-level confrontation in the region.

WHAT IS THE SITUATION RIGHT NOW?

On Sunday 7 July, Tehran officially declared its intention to scale back on the limitations of the Iran nuclear deal for a second time by breaching the 3,7% enrichment threshold established in the agreement. The new enrichment level of 5%, however, is still far from one that would indicate non-civilian use.

The Iranian authorities, moreover, signalled their intention to continue to gradually reduce the compliance to the deal at a 60-day rate, unless a feasible solution is reached to safeguard Iran against the crippling US sanctions and guarantee the survival of the agreement itself. This represents the first radical escalation since Washington’s withdrawal from the agreement on 8 May 2018 and, although deliberately minimal, it drew international condemnation, both from the deal’s signatories and regional stakeholders such as Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Although still far from the 90% enrichment levels that would be necessary to weaponise the uranium, Iran is showing its intention to retaliate to the recent increase in sanctions imposed by the US, which virtually eliminated its oil revenue completely by slashing the waiver for some countries to import oil, steel or copper from Tehran. All sides have repeatedly declared a willingness to talk and negotiate, but the bilateral rhetoric between the US and Iran is only showing signs of escalation, while the recurring talks in Vienna with the remaining members of the deal suggest little chance of a permanent solution

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), global nuclear watchdog, had officially deemed Iran compliant with the agreement, which it remained for one full year after the American withdrawal. In an attempt to save the deal in the absence of one of its biggest stakeholders, the EU promised Tehran a solution to make up for the large losses in revenue that the US imposed sanctions were producing, which caused a rise in inflation and drove away the international investments that Iran had managed to regain.

However, the imposition of even more stringent sanctions and the hostile diplomacy from President Trump, who declared Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) a terrorist group and accused Iran of conducting a covert campaign against the Arab oil exports, fundamentally frustrated any attempt by the EU to make compliance to the deal seem less one-sided for Tehran. The main motivators for Iran’s participation to the deal were, in fact, a desire to establish itself as a source of stability in the region and escape the mounting UN and internationally imposed sanctions that were damaging key sectors, crippling its economy and, by extension, weakening the self-preservation of its leadership.

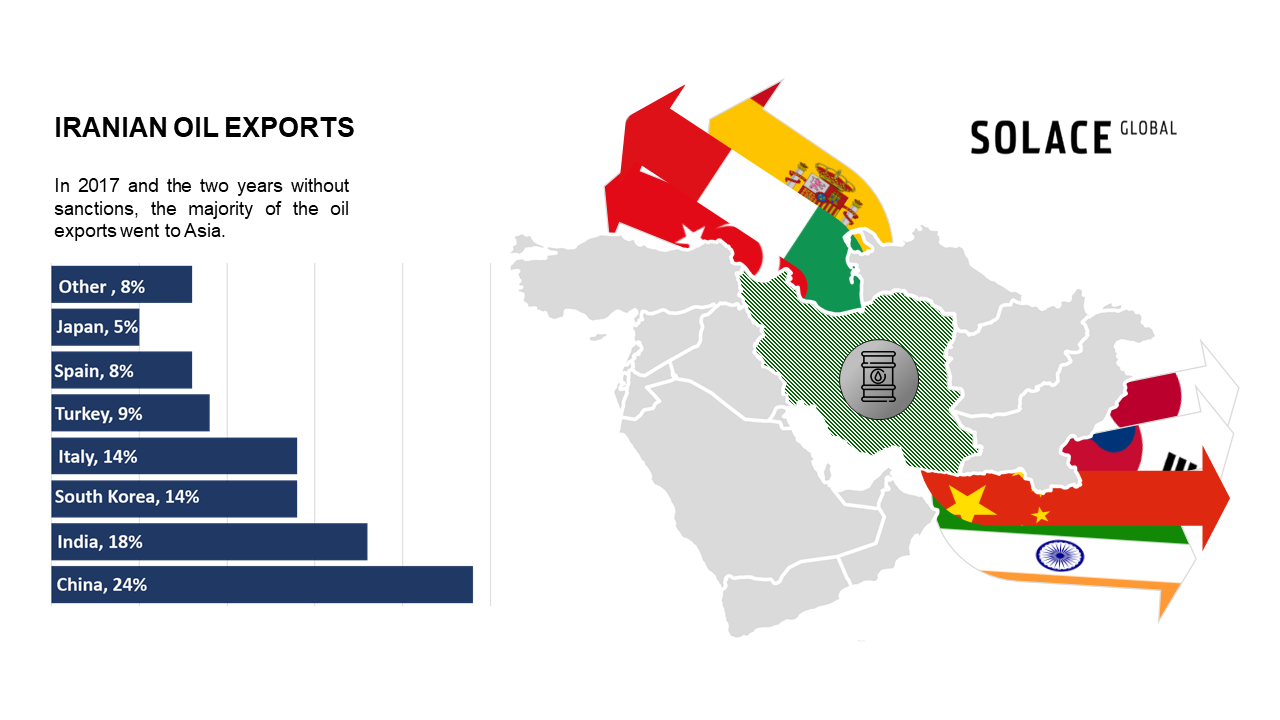

The recent decision by Washington to create an oil embargo against Iran fundamentally undermined the EU’s effort to keep the deal intact, by making it impossible to match the same levels of revenue that Iran could achieve through the oil trade, which is likely to ultimately cause the agreement to cease. This damages the future multilateral efforts towards effective counterproliferation: by depicting both the EU and the US as unreliable stakeholders, whose commitment can vary depending on the current administration, President Trump showed the inherent reversibility of any commitment towards the lifting of sanctions, which has a very different time-frame compared to the development of nuclear weaponry.

In the past two years, Iran has seen a significant level of unrest and insurgency at a domestic level, culminating with the wave of economic protests that broke out in December 2017 and that continued through the following year, slowly turning economic grievances into a criticism of Tehran’s theocratic regime.

The support for the regime’s foreign endeavours, such as the nuclear deal and the war in Syria is eroding as the population grows frustrated with the economic stagnation. At the same time, hardliners in Tehran’s political and military establishment are gaining power as their accusations of an attempt by Washington to cause a regime change are reinforced by Trump’s “extreme pressure” policy. Iran’s leadership finds itself faced with a conundrum where finding a solution to the American’s oil embargo is paramount, but where an absence of retaliation to Washington’s hostility would be viewed as an international show of weakness. The decision to gradually reduce its compliance to the deal is fundamentally driven by a desire not to antagonize the EU, Russia and China, and face economic and political isolation, whilst also signalling the urgent need to find a solution feasible for all participants.

WHAT COMES NEXT?

In the event of a collapse of the nuclear deal, the consequences will reach far beyond the participating states: Iran has already signalled that it is unlikely to unilaterally uphold the constraints on its nuclear programme in the absence of the benefits provided by the multilateral agreement. Likewise, its regional rivals, namely Israel and Saudi Arabia, will show little tolerance towards an attempt to gain even a nuclear ready status, the latter having already declared its willingness to pursue nuclearisation. Instability in the Middle East, due to its complex network of national and religious allegiances, as well as ongoing conflicts and endemic issues, has immediate repercussion on virtually every continent in the world.

Some of the key areas being impacted by the recent developments has been the oil and gas, as well as the maritime industries: since the decision by President Trump to remove the waiver to allow Iran’s biggest importers to continue purchasing oil on 2 May, two distinct incidents took place in the space of a month in the vicinity of the Strait of Hormuz. The US and Saudi Arabia immediately attributed the incidents to Iran, namely due to its interest in disrupting oil trade by regional competitors and the use of mines, a modus operandi reminiscent of the 1980s Tanker War. However, due to the timing of the incidents, the second of which taking place in the midst of a historical state visit of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to Tehran with the stated purpose of facilitating a solution for the nuclear deal, it seems unlikely that Iran would deliberately show itself as a hostile force.

Regardless of the actual culpability, in the event of a complete collapse of the nuclear deal and a continued oil embargo pushed forward by Washington, Iran might indeed choose to target the oil trade and, in a worst-case scenario, attempt to blockade the Strait.

The EU, which has seen first-hand the consequences of instability and war in the Middle East, has a vested interest in avoiding an escalation and its impact on Islamic militancy and the refugee influx, which are already compromising the very fabric of the Union. Moreover, a nuclear arms race in such vicinity presents a grave security concern: while it is unlikely for Tehran to directly threaten the European region, the establishment of a system of nuclear deterrence between Iran, Saudi Arabia and Israel would be probably irreversible and result in low-level confrontation in a similar fashion to the India-Pakistan nuclear impasse.

Due to the prospect of the international isolation that would come with an immediate attempt to develop nuclear weaponry, which could even result in direct confrontation with the US and its regional allies, it is also unlikely that Tehran would decide to pursue that strategy immediately after the collapse of the deal. Instead, it might decide to continue a policy of gradually increasing enrichment up to 20% “highly enriched” uranium, insufficient for weaponisation but enough to be employed for medical and research purposes. This would potentially give Tehran enough to leverage some type of breathing space for its oil and banking industry, possibly by gaining the support of Russia and China, with the latter being heavily reliant on oil imports.