Evacuations from Israel and High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

Implications of Brexit on Travel

18 Feb 2019

With the details of Britain’s exit from the EU remaining unclear, the potential impact on travel also remains unclear. The report gives an outline of the potential impact on travel after the UK leaves the EU on 29 March.

Key Points

- Britain is set to leave the European Union at 23:00 UK time on 29 March (midnight in Brussels).

- While the British government and Brussels have agreed to a deal, this deal has not been approved by parliament. This means that, with less than two months left; the actual terms of Britain’s exit remain unclear.

- With the details of the exit remaining unclear, the potential impact on travel also remains unclear.

- Outlined below is an overview of this potential impact on travel after the UK leaves the EU on 29 March.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

As Brexit negotiations enter a critical stage, a large number of questions related to the ease of movement and goods across UK and EU borders remain unanswered, and in particular the implications of the deal – regardless of its eventual outcome – on both corporate and personal travel. The prospect of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit exacerbates these uncertainties, with considerations including increased travel costs, the potential need for travel and work visas, lengthy border and immigration controls, and most critically, the possibility that UK and EU passenger transport operators might have to scale down operations, or could lose the right to operate, between and within the two areas.

Besides implications for rail, air, sea and road travel between the UK and EU, Brexit has also raised concerns over its ramifications on international air travel as the withdrawal from the EU could force airlines to review existing agreements allowing the use of the UK as a transit hub. Although a remote scenario at present, a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland – should the ‘backstop’ be removed from the final deal – would pose immediate challenges in terms of travel, and, potentially, security.

Brussels and London have every interest in minimising the impact of Brexit on travel. In the absence of concrete advances in the negotiations, however, there are strong concerns that the vote could, at least initially, result in severe disruption and additional operational costs for businesses and travellers when and if Brexit is fully implemented.

CURRENT SITUATION

On 25 November, the 27 European Union leaders unanimously endorsed the UK’s Withdrawal Agreement, which sets out the terms of the UK’s exit from the EU, and the Political Declaration setting out the basis of the future relationship after Brexit, notably with regard to trade and security.

The Withdrawal Agreement was rejected by a record majority of 230 MPs on 15 January. Three main scenarios are possible – attempting to renegotiate (although the EU has rejected such option), leaving with ‘no deal’, or a second referendum. Should the first scenario materialise, the UK and the EU could consider changing the Political Declaration and push for the UK to join the European Free Trade Association (EFTA, which includes Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Liechtenstein) and stay in a permanent customs union – which would maintain freedom of movement to and within the European Economic Area (EEA). This ‘soft Brexit’ option would be geared towards a “Norway plus” plan, which a cross-party group of MPs and EU Brexit Negotiator Michel Barnier have been advocating. The option would also limit the impact of Brexit on travel. However, a number of Brexiteers object to the Norway Plus plan given the lack of guarantees with would entail in terms of customs arrangements, free movement and trade deals.

INITIAL IMPACT ON TRAVEL

While it is difficult at present to effectively assess the full impact Brexit will have on business and travel – leaving aside potential ramifications on security, the economy and political stability – all scenarios entail a degree of disruption to business continuity, with ramifications for corporate travel and the supply chain. Illustrating concerns over a ‘no-deal’ scenario, the UK government on 24 September 2018 issued 25 technical notices outlining guidance for people and businesses – including with regard to travel – to prepare for a potential ‘no-deal’ outcome.

Prime Minister Theresa May has ruled out membership of the single market, and warned that freedom of movement will end when the UK leaves the bloc. Unless all areas of concern are resolved within the 21-month transition period, which ends in December 2020, considerable changes and delays should be expected for business travellers after 29 March 2019, when the UK transitions into ‘third country’ status. The transition period, however, is part of the withdrawal agreement. In the event of a ‘no deal’ scenario, free movement of people would stop immediately on 29 March 2019.

The UK is preparing to leave the EU at a time when Brussels is working towards the launch of the European Travel Information Authorisation System (ETIAS), aimed to strengthen the EU’s external borders. The measure will apply to all visa-exempt countries outside of the EU (except those in the EEA/EFTA system, which maintain free movement within the EU) coming into the Schengen area, which the UK is not part of. Applicants, which will include British passport holders once the UK leaves the EU, will have to fill out an online application form detailing the applicant’s occupation, health, travel itinerary and any criminal records, among others, prior to travel to any of the EU member states. The data will then be checked against EU police and Interpol databases. Once granted, the authorisation, which will cost EUR5, will be valid for five years or until the applicant’s passport expires. ETIAS is scheduled to come into force by 2021. Airlines and ferry lines will be asked to check that non-EU travellers do hold an ETIAS authorisation. Coach operators are also scheduled to implement the programme three years after the introduction of the scheme.

CONSIDERATIONS ON AIR, ROAD AND RAIL TRAVEL

Air travel

The UK’s geographic position makes the country extremely dependent on air and rail transport for travel into/from Europe. The UK has the third largest aviation network in the world, and the largest in Europe. In 2017, 76 percent of international passenger movements at UK airports were to/from European countries, 164 million passengers travelled between the UK and other EU countries by air, and UK travellers represent around 25 percent of all European passengers. The aviation sector could be one of the worst-hit in the absence of an agreement in place before 29 March 2019, with some major markets and routes potentially severely affected. This could be the case for UK-Spain flights, which currently number more than 5,000 a week.

While this appears, an unlikely scenario given the level of disruption this would generate, a number of businesses and representatives of the aviation industry have warned that, in a ‘no deal’ scenario, flights would cease to operate between the UK and the rest of the EU. This would impact UK-registered aircraft but also aircraft made with UK-made parts, which, for the time being, are certified by the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), which sets rules and regulations for the safe operation of civil aviation in Europe, and which the UK is a member of. If the UK leaves the EU without a deal, the country will, in theory, lose membership to EASA, and in the absence of internationally-recognised safety certificates, any aircraft using UK-made parts could be grounded.

Moreover, after Brexit, the UK will still be a member of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), which cooperates with EASA on a wide range of activities, including safety. Although EU membership is not a prerequisite for EASA participation, the UK aviation industry will have to ensure arrangements are in place to retain EASA membership. The ability of EU operators to fly into and within the UK will depend on the type of Brexit that is ultimately concluded, and on which rules subsequently implemented. In the event of a ‘no-deal’ scenario, UK operators, even those owned fully or in part by European companies, might lose their “community air carrier” status and rights to operate within the EU. Those operators would then need to be granted foreign airlines permission from national aviation authorities in the relevant EU countries in order to operate to and within those countries. Meanwhile, EU carriers wishing to operate to and within the UK will also be considered third country operators (TCOs) and will need a Foreign Carrier Permit delivered by the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA).

Upon leaving the EU, the UK would lose access to the EU’s “open skies” arrangements, whereby EU airlines can operate freely between any two locations in Europe – without the aircraft having to touch down in the country the airline is based and registered in. The agreement also enables EU or US-based airlines to fly any transatlantic route between the two geographic zones. Currently, some 80 percent of all North Atlantic traffic passes through UK or Irish controlled airspace. In the event of a ‘no-deal’ scenario, the UK will have to negotiate new, or try and revive old, bilateral arrangements with those non-EU countries.

In view of those potential changes and challenges, agreements relating to flying rights, airline ownership and business registration authority, operating licenses, route authorisations, safety certifications and regulations, including passenger rights, would have to be concluded before the UK leaves the EU to facilitate a smooth transition post-Brexit and limit disruption. The uncertainty surrounding the type of agreement that will ultimately be implemented makes it difficult, however, for airlines and aviation authorities to adequately prepare, raising the risk of disruption to air transport should the UK leave without a deal – in which case EU law will again, in theory, cease to apply immediately, in the absence of transition period, and in the absence of precedent or World Trade Organisation framework in this field.

Potential impact

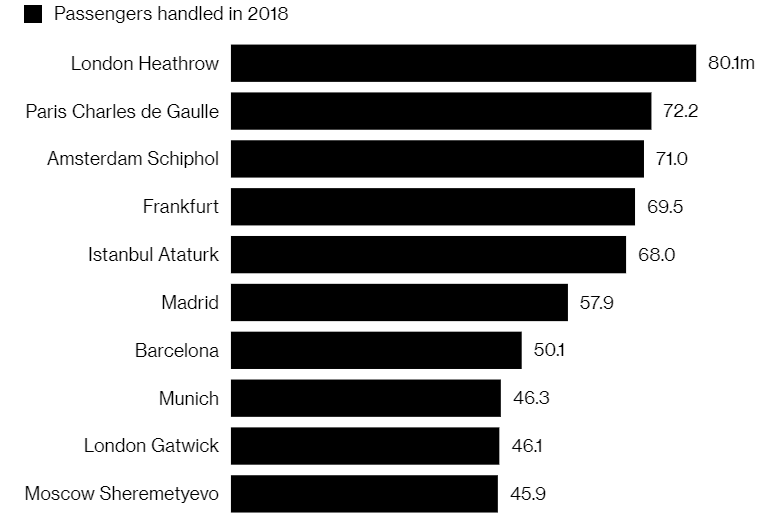

There are strong concerns over the impact of a ‘no-deal’ on the aviation sector. However, the UK, and London in particular, is a major international aviation hub, London Heathrow is the busiest European airport, with London Gatwick the ninth busiest airport in the EU, and large-scale disruption is unlikely. Both Brussels and London have already stated that mechanisms are in place to grant permission to EU airlines to continue operations. However, the EU is yet to confirm whether it would reciprocate. This will increase cost for airlines, limit the scope for expansion and growth opportunities, and reduce competitive prices and flexibility for customers.

Source: Bloomberg

Travel organisations and the Department for Transport (DoT) state that passengers can “book with confidence” and that flights will continue as normal in the event of a ‘no-deal’. The European Commission has for its part offered a “bare bones” agreement on flights continuing between the UK and EU in the event of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit. However, ratings agency Moody’s has warned that airlines are one of four sectors most at risk from a ‘no-deal’ Brexit and even if a transition phase is agreed for the period after March 2019, a high degree of uncertainty remains for the aviation sector. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) has also warned of a potential cap on UK flights to the EU in the event of a ‘no-deal’. Should this materialise, flights on UK airlines to each EU country will be capped at summer 2018 levels, which means that flights, likely to be new routes or departures, would need to be cancelled to comply with the new regulation. Air travel from the UK to the EU was expected to significantly expand this year – up to five million extra seats were scheduled for 2019 compared with 2018. EU carriers should not be affected, unless the UK government decides to reciprocate by imposing its own cap on EU airlines. Airports might also have to change passenger flows in the event of a ‘no-deal’ scenario.

With regard to travel requirements, the UK government is at present not planning to ask EU travellers to apply for visas, and is hoping for reciprocity, and the European Commission has proposed visa-free travel for UK visitors to the EU, provided the UK reciprocates. Regardless of the outcome of the negotiations, however, the UK will acquire ‘third country’ status after 29 March 2019 or after the transition period, which would, in theory, compel UK travellers to go through additional screening – and potential rescreening of passengers and luggage for transfers between European airports. Airport authorities are working to minimise disruption, but process times are expected to be lengthier as there will presumably no longer be a “blue channel” for travellers arriving from the EU at UK airports after Brexit, and UK travellers will also no longer be able to use the EU fast-track lanes at European airports.

The impact is expected to be particularly acute at major transit hubs such as Amsterdam’s Schiphol International Airport, where customs is recruiting 930 additional staff to screen passenger items and cargo flights once Brexit is implemented. The UK also plans to hire some 1,000 new customs and immigration staff to ensure border security after Brexit as the UK’s withdrawal from the EU will result in a major overhaul of security and immigration procedures for border control. This also raises security concerns as resources might be initially diverted to the management of passenger arrivals and immigration, as there will presumably no longer be an EU channel at UK airports, which could be to the detriment to security and screening processes at all sea and airports as well as land borders. Illustrating concerns over the impact of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit on ports and airports, in mid-January France triggered a contingency plan in the event of a “hard Brexit”. This includes the recruitment of some 600 new staff – including customs officers, government officials and veterinarians – in the coming weeks, and EUR50 million of investment to assist ports and airports.

These additional requirements are expected to have a significant impact on airfares as operators will have to compensate for higher licencing and operating costs, especially if UK-based companies, including low-cost airlines, decide to relocate all or part of their operations to Europe. EasyJet, which in 2017 created a new airline based in Vienna to keep its EU planes flying after Brexit, has already registered 110 aircraft to the new unit and has started to move its pilots based in mainland Europe to Austrian and German contracts, amid concerns that pilot licences issued by the UK may not be valid within the EU post-Brexit. Pilots might also have to obtain two licences to be able to operate in both the UK and within the EU.

Additional costs and requirements, such as higher prices and exchange rates, more restrictive processes and procedures, longer travel times/schedules and the potential need for work visas, might prompt businesses to streamline overseas operations and travel, which could in turn impact prices as changes in habits could alter supply and demand and drive fares up, especially in the absence of competition – and choices for travellers.

Road travel

Ireland

The controversial question of the border ‘backstop’, a position of last resort to maintain an open border in Ireland should the UK exit the EU without securing an all-encompassing deal, remains the main point of contention between the negotiating parties. The backstop, part of the Withdrawal Agreement, maintains Northern Ireland in the EU customs union, thereby pushing checks and controls to sea and air entry points to Ireland.

Both the UK and the EU want to avoid a hard border but leaving the single market and the customs union without any new arrangement in place would change the status of the Irish border to that of a customs border and would require the implementation of physical checks or infrastructure between Northern Ireland and Ireland.

While the UK has said that “smart border” technology would be introduced should that scenario materialise, this is unlikely to be sufficient to monitor regulatory compliance and physical movement between Europe (Ireland) and the UK (Northern Ireland), which would have immediate repercussions on travel across the border. However, this would require significant investments, time and development, and the technology that would be needed is not operational.

Travel in Europe

Brexit will also have implications for road travel into and within the EU. In the event of a ‘no-deal’, the UK driving licence may no longer be valid, or sufficient, when driving in the EU. UK travellers would need to carry their Green Card – proof of insurance cover – to travel in the EU but might also need to obtain an International Driving Permit (IDP) to drive in the EU, both for leisure and business purposes, including for car hires. Two types of IDP currently exist within the EU, depending on the country, and both are required for non-EU travellers visiting EU countries covered by different conventions.

UK coach operators, such as National Express, are particularly at risk and have been advised to consider subcontracting “all or part of the coach travel” in Europe to EU-based operators as a ‘no deal’ Brexit would mean operators could no longer rely on automatic recognition by the EU of community licences issued by the UK. International coach companies should not be affected, however.

Travel to the UK

Arrangements for EU licence holders visiting the UK should, in theory, stay as they are, although restrictions may apply to driving licence exchanges for EU nationals moving to the UK on a temporary or permanent basis. Insurance costs might also increase for both EU and UK nationals wishing to drive in the UK/EU.

Potential impact

For both freight and passenger traffic, delays should also be expected at Dover and Calais ports for additional customs checks, passenger controls, vehicle authorisation, and administrative procedures, which in turn will also increase export and import prices.

With regard to travel between Ireland and Northern Ireland, no passports should be needed after the UK leaves the EU as per the terms of the Common Travel Area, which applies to the UK, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. However, individual airlines might require passports for commercial purposes. Removing the backstop from the Withdrawal Agreement, although an unlikely scenario, would also complicate, and potentially overhaul, all agreements in place.

Rail travel

The UK and EU members states, in particular, France, Belgium and the Netherlands, will want to ensure that cross-border rail services, including Eurostar, Eurotunnel but also Belfast-Dublin Enterprise services, continue operating without disruption. More than 10 million passengers travelled on the Eurostar in 2017, and the Eurotunnel’s passenger and freight shuttle carried 2.6 million passenger vehicles, 1.6 million heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) and 51,000 coaches in 2017.

Potential impact

Rail travel is expected to be the area less impacted by Brexit as individual agreements are struck with European countries, and railway operators in the UK and the EU tend to set up subsidiaries in the relevant countries. Disruption should also be minimal in terms of security checks as all travellers on the Eurostar must already pass through customs for both the UK and the EU before boarding a train.

However, should the UK leave the EU without securing an agreement, operating licences and certificates issued by the Office of Rail and Road (ORR), the UK’s safety authority, to railway operators running services in the EU would no longer be valid after Brexit. French and Belgian authorities last year warned that, in the absence of a deal and no contingency plans, Eurostar trains could be stopped on reaching their territories, which also partly triggered the French government’s decision to allocate EUR50 million to border security.

A main concern stems from divergence in the interoperability or safety standards between the UK and the EU, and the UK will have to update domestic legislation to adjust to related regulations. Delays should be expected as extra security checks might need to be implemented post-Brexit as a result.

Secondary implications

Besides implications on travel costs, Brexit might have an impact on a number of services associated with travel to/from the EU, notably consumer protection and passengers’ rights for flights operated by UK carriers departing from the UK to the EU, roaming charges, and medical insurance. Technically, the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC), which entitles UK national to free, or affordable public health care in the EU, will no longer apply once the UK leaves the EU.

Potential Impact

At this stage, it is unclear whether mobile phone providers might reintroduce roaming charges for UK travellers in the EU, and European nationals travelling in the UK. Under the Withdrawal Agreement, EU regulations, which currently limit roaming charges, would apply until the end of the transition period. However, upon leaving the EU, the UK will also leave the EU’s Digital Single Market. Thus far, network provider Three have stated that they would continue to allow UK customers to roam free of charge as part of their Go Roam offering.

The impact of the loss of EHIC should be limited as the card currently only entitles UK nationals to free emergency care. However, this could impact health insurance premiums for UK nationals travelling or working in the EU.