Evacuations from High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

Global Impact of Ukraine Invasion: The Russian Periphery

28 Apr 2022

The war in Ukraine will have an impact on a number of states within the Russian near abroad. Many of these states often have an uneasy history with Russia.

This is the third report in the series showing theglobal impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and will examine some of these countries and how they have been impacted.

Executive Summary

The war in Ukraine will have an impact on a number of states within the Russian near abroad. Many of these states often have an uneasy history with Russia. Some states are NATO members, others have large Russian-speaking minorities, at least two are home to Russian-backed separatist movements, whilst others area heavily dependent on the Russian economy.

All these nations have experienced political angst as a result of the invasion. How these countries have been impacted by the Russian invasion varies dependent on their exact circumstances and relationship with Russia.

This is the third and final report into the global impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and will examine some of these countries and how they have been impacted.

Scandinavia

At the end of the Second World War, Finland became the only independent territory of the Russian Empire that was not annexed into either the USSR or the Eastern Bloc. In 1948 the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance between Finland and the USSR (United Socialist Soviet Republic) was signed. This resulted in the establishment of Finland’s neutral status throughout the Cold War. This agreement formed the basis for Finnish foreign policy towards both the USSR and the West until its replacement in 1992 with the Russia – Friendship Treaty. Meanwhile, Sweden adopted a neutral and non-aligned foreign policy position in 1949.

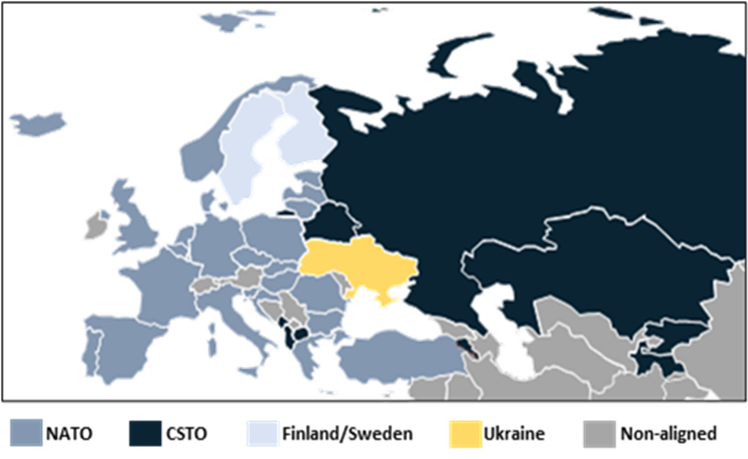

The neutral and non-aligned status quo in both nations, which had the support of most citizens, has been completely disrupted because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In mid-March, surveys in Finland showed for the first time ever a clear majority of sixty-two percent supporting Finland joining NATO. Three years ago, when the question was last asked in Finland, only nineteen percent supported NATO accession. In Sweden, a similar poll found support at fifty-one percent, up from thirty-seven percent in January 2022. These twin sudden shifts with regards to NATO membership are likely to generate a wholesale shift in the wider European security landscape.

Whilst at the time of writing, the change in opinion is occurring quicker in Finland than in Sweden, it is widely speculated that both countries would seek accession to the alliance at the same time, in a joint bid. In April 2022 it was announced that both Finland and Sweden were looking to lodge their NATO applications by the middle of May.

The prospect of these two formerly neutral and non-aligned states seeking to join NATO will lead to further inflammation of the wider relationship between NATO and Russia, since if the accession occurs the NATO-Russia border would become around 1,600 miles long and would effectively surround the strategic Russian port of Murmansk. It would also mean that the Baltic Sea and Gulf of Finland, which leads into St. Petersburg, would be surrounded by NATO states. St Petersburg contains a strategically important port, whilst the city itself is historically significant to Russia. Russia is likely to perceive NATO encroachment in the Baltic Sea as a legitimate threat to maritime operations, which would undoubtedly contribute to Russia’s narrative of NATO expansionism as an existential threat. Whilst it is believed that the possibility of NATO membership for Ukraine contributed to the Russian invasion, it is unlikely that Russia would greet the accession of these two countries to NATO with the same hostility. This is most likely because neither are seen as being historically within the Russian sphere of influence. Despite this, Russia has repeatedly warned that the West would suffer “serious military consequences” in the event the two nations joined NATO. Indeed, in April 2022, Russia announced if the two Nordic countries joined NATO, then they would deploy nuclear weapons to Kaliningrad. This threat can be taken with some cynicism given Russia is already widely suspected of keeping nuclear warheads in the exclave. However, it does demonstrate that for Russia, the threat of nuclear weapons is an increasingly standard response and one of President Putin’s true levers of power.

The ramifications of such a NATO accession will be felt more broadly in the continued decline of the wider Russia – West relationship. Finland and Sweden have stated they are both “prepared” for a reaction from Russia. Such a reaction is likely to come in the form of unconventional warfare. This includes information warfare, the use of disinformation within Sweden and Finland, and the use of cyber attacks with a veneer of plausible deniability. Other consequences are likely to include further militarisation of the Finnish-Russian border, including an increased frequency of military training exercises in the Kola Peninsula region, deployment of strategic missile forces, anti-access and aerial denial (A2AD) systems and border surveillance/reconnaissance flights. On 13 April, in response to the discussion around NATO membership, Russia has begun sending K-300P Bastion-P mobile coastal defence systems to the border in the first sign of such a militarisation of the border.

The Baltic States

Part of Putin’s justification for the invasion of Ukraine has been the concept of Russkiy Mir, or the Russian World. This is the idea that following the dissolution of the USSR and its predecessor the Russian Empire, Russians and Russian speakers live in a “divided nation” and that under Putin and Russkiy Mir, these divided Russians will be reunited into one Russia. With the dissolution of the USSR, around twenty-five million Russians and Russian speakers found themselves outside Russia’s contemporary territorial borders. Russkiy Mir as a concept evolved in the late 1990s and has, to an extent, been driving Russian foreign policy ever since. The Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, all with large Russian minorities and who only gained their independence from Russia with the end of the Cold War, have often stated that Russia is their most existential threat. Despite this, until the invasion of Ukraine this fear was not taken as seriously as perhaps it should have been. Indeed, in the wake of the Ukraine invasion, the Estonian and Latvian Prime Ministers said the West’s previous attitude to Russia was based on a “naivety” which had now been exposed.

In Estonia, around twenty-five percent of the population speak Russian as their first language, whilst in Latvia it is around thirty-seven percent, and in Lithuania this percentage sits at around fifteen percent. These relatively high percentages generate concern in all three states that they could be the target of Russian aggression in some form, particularly influence and information operations. Alongside this, the three countries share a high percentage of residents who are ethnically Russian – resulting from years of Russification which the three nations experienced during their time first as part of the Russian Empire and then subsequently the USSR. Proportions of ethnic Russians within the three countries can be seen below. Perceptions that the Baltic region is isolated from the rest of NATO geographically, via the strategic chokepoint at Suwalki, only serve to amplify this feeling of insecurity.

Estonia shares a long land border with Russia, although as much of this crosses Lake Peipus, realistically there are only two axes of advance for conventional Russian ground forces. Latvia meanwhile shares land borders with both Russia and its ally and “Union State” partner, Belarus. Lithuania also borders Belarus, and the heavily militarised Russian exclave of Kaliningrad. As a result of this geography the three Baltic states are only connected to the rest of NATO by a sixty-five-kilometre-long border between Lithuania and Poland known as the Suwalki Gap. Belarus and Kaliningrad respectively bound this gap to the East and the West. The gap is widely assessed to be one of the weakest defensive points for all of NATO; it contains three road crossings and one railroad and as such is a definite choke point for NATO defensive operations in the Baltics.

Whilst the Baltic states may once again feel insecure, counterintuitively, their membership of NATO means that unlike Ukraine they are more secure than they have ever been. NATO membership certainly negates any possible Russian invasion, barring a highly unlikely escalation of conflict into a broader war across the European theatre The combination of geography and linguistics means that all three countries are territories where the defence of NATO and its shared values will either succeed or fail – in this manner the region becomes comparable to West Berlin in the twentieth century.

The security threat in this region is most likely to manifest as Russian unconventional warfare and destabilisation activities. In 2007, Estonia received a forestate of what such destabilisation efforts could achieve, when Russian language media outlets in the country instigated a two-day riot in Tallinn which led to over one hundred wounded and was directly followed by cyber attacks on the country’s banking system, government agencies and Estonian language media eco-system – effectively paralysing Estonia. There is also the high probability that the Baltics will see sophisticated Russian information campaigns targeting their populations, which have most likely been ongoing to some extent since their independence. In 2019, a news agency in Latvia known as BaltNews was closed after it was revealed that it was financed ultimately (through several opaque shell structures) by the Russian state media company RIA Novosti. Meanwhile, the Chair of the Latvian National Security Committee has stated that across the Baltics there are at least one hundred NGOs operating across the Baltic states that are financed by Russian state. These NGOs, whilst they participate in the liberal and civic discourse of the Baltic democracies enable the Russian government to have insight into Baltic state democracies, and to some extent allows Russian influence and money to work within the system – often creating anti-NATO or anti-Western discourse and platforms.

Aside from information operations or political subterfuge, a large-scale cyber-attack on critical networks or infrastructure should also be considered a major security threat in the Baltics. At the time of writing, there is an unresolved debate within NATO as to whether a cyber-attack would meet the threshold to trigger Article 5 and how destructive that attack would have to be in order to do so. Alongside these more destructive activities, the Baltics are likely to see the use of Russian soft power amongst the Russian speaking minorities. All three Baltic states have in recent years faced challenges from Moscow’s “compatriot policies” which extend Russian citizenship rights and passports to Russian speakers outside of Russia and which also generally aim to try and destabilise national political coherence.

Whilst the concern against such destabilisation activities in the Baltics is real, as is the fear that the Russian speaking minority may be more susceptible to them, national governments will need to carefully ensure that the Russian speaking minorities are not seen as something akin to a “fifth column”. It should not be assumed that speaking Russian automatically means that you support a revanchist Russia and the idea of Russkiy Mir. Making such assumptions about the large Russian speaking minority in the Baltics may well be counterproductive and only exacerbate tensions between the Russian speaking minorities and the majoritarian linguistic groups. It must also be noted here that the Baltic states have in recent years realised the latent threat that Russian language media could pose. For example, in 2015 Estonia’s public broadcaster launched a Russian language subsidiary aimed to providing a service to those Estonians whose first language is Russian and may otherwise get their news and entertainment from Russian state-controlled media.

Whilst the threats posed to the Baltic states from Russian disinformation can not be easily remedied, perceptions of geographical isolation would be removed if Finland and Sweden were to both ascend to NATO. This fact is why the Baltic leaders are some of the largest supporters of such a move – with the Lithuanian President, urging both nations to “not waste time in applying.”

Eastern Europe

Across wider Eastern Europe there are a number of countries which may be impacted in the longer term, with Moldova and Bulgaria the most susceptible. In Bulgaria, the war has exposed the extent of Russian influence in the country and has begun to lead to questions about what the country, which is a NATO and EU member state, should do to try and reverse this process. Russian influence in Bulgaria is not a historical anomaly. The country is home to one of the largest populations of Russian speakers outside of Russia. It is estimated that around thirty-five percent of Bulgarians speak Russian and so close and longstanding were the cultural and economic ties between Russia and Bulgaria that during the Cold War, Bulgaria was seen as the sixteenth republic of the USSR. Since the fall of Communism, such links persisted as they had been founded on robust cultural, religious, and historical ties.

In recent years this has meant that much of the Bulgarian media, economy and political elite has had ties to Russia and Russian oligarchs, whilst the country’s notorious corruption problem has often enabled those ties to go unscrutinised and to be further exploited. As a result, Bulgaria is the EU country most vulnerable to Russian interference, and Russia has, in the words of the Bulgarian Center for the Study of Democracy, “unparalleled” influence in the country. At the time of writing, the country’s ruling government includes the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), an avowed Pro-Russian and pro-Putin party, and recent decades of government policy have often been a delicate balancing act – aiming to displace neither Moscow nor the West.

As a result of the fact that Russian is so widely spoken, whilst cultural and political ties are strong, Bulgaria has become a fertile breeding ground for both external Russian disinformation and endemic pro-Russian propaganda and disinformation. Kremlin aligned Russian oligarchs, such as Delyan Peevski, are known to own a selection of Bulgaria’s largest and most well used media outlets. More widely, Russia also plays an outsized role in the Bulgarian economy, with it being estimated that around a quarter of the country’s GDP is linked to Russia or Russian owned entities.

These are all issues which have become more apparent since the Ukraine invasion, and as a result the governing coalition in Bulgaria is spilt on the issue of how to effectively respond to the Ukraine invasion. Prime Minister Kiril Petkov is staunchly pro-EU, yet he and his party govern in coalition with the BSP. The spilt in the government meant that within days of the invasion commencing the Prime Minister had to fire his Defence Minister, Stefan Yanev, because Mr Yanev described the invasion as an anti-fascist special operation – effectively emulating rhetoric employed by the Russian state.

The invasion of Ukraine has for many Bulgarians highlighted the fact that their state, economy and media are all much more pliant with regard to Russia than many of their fellow EU and NATO counterparts. Like many EU nations, Bulgaria has seen large scale anti-war demonstrations take place across the country. Due to the ties between Russia and Bulgaria, however, these protests should be seen in a different light to those across the rest of Europe, as the protests in Bulgaria come against the backdrop of a national realisation of just how entrenched Russia remains within Bulgaria.

The war has also led to a notable decrease in Bulgarian support for Putin, dropping from fifty-five percent of the country to thirty-two percent. This drop has been accompanied by a surge in support for Bulgarians believing that their country is best served by remaining in the EU and NATO – which has risen to sixty-three percent, whilst those saying Russia is a model state has fallen to fifteen percent. These statistics, and the fact that Bulgaria is now openly looking at removing and relocating Soviet-era memorials and changing soviet era public holidays and place names, can be seen as signs that Bulgaria is on the cusp of a historic cultural transformation. In time, this will likely affect the geopolitical stance of Bulgaria, which as indicated has hitherto tried to balance between both the EU and Moscow.

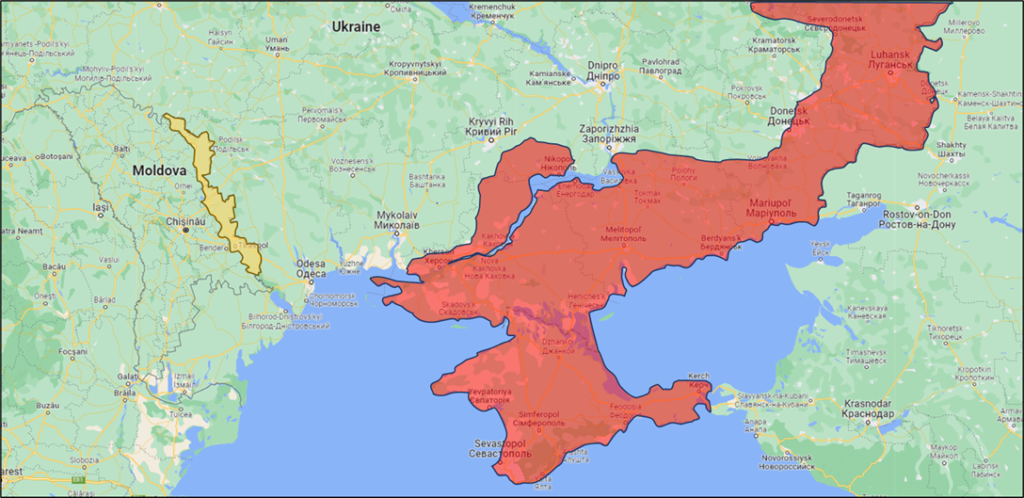

Bordering Bulgaria is Moldova. This is Europe’s poorest country, and it is not a member of either NATO or the EU. It is, however, home to Russian backed separatists. The confluence of these factors means that it is often seen as sharing a similar profile to that of Ukraine. Russian backed separatists control an area of land known as Transnistria, which they officially claim as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR). The land it occupies is a narrow corridor that runs along the east bank of the Dniester River in Moldova parallel to the Ukrainian border. Significantly, it is situated within about twenty-five miles of the Ukrainian port city of Odessa. This breakaway territory was proclaimed in 1992 after the signing of a ceasefire which brought about the end of the Transnistria war. Russia supports the self-proclaimed republic and is believed to have sent approximately 1,500 Russian troops to the area alongside military equipment.

As Russia increasingly looks to have failed in its bid for a short, sharp war in Ukraine, it is possible that attention may turn to Transnistria. Russia could recognise the region as an independent state or it could become the focus point of a so-called false flag event, manufactured by Russia to justify an intervention. Both options, if successful, would generate significant propaganda for the Russian state. If the former were to occur it would be seen as a significant indicator that Russia may well be preparing to expand the geographical scope of the conflict from outside Ukraine, and into other areas which could be seen as part of the “Russkiy Mir.”

Even if there were no moves to recognise Transnistria as independent by Russia or to try and bring the territory into some form of wider conflict, the fact that the Russian military may be seeking to occupy Odessa is of concern for Moldova. It remains realistically possible that Russia may seek to create a land corridor between the Russian backed territories of Transnistria, Donetsk, Luhansk, annexed Crimea and wider Russia. If such a corridor was to come to fruition, then the relative calm which has held in Transnistria since the 1992 ceasefire may end, as the balance of power and geography would have tilted in favour of Transnistria. If such a Russian-controlled corridor is created, then it may also spur Transnistrian politicians to call for Moscow once again to formally annex the territory. The current President, Vadim Krasnoselsky, has previously called for such action to be taken. The lack of contiguous borders between Russia or Russian controlled territory is likely to have been a factor which had led Russia to not annex Transnistria previously – however, if they succeed in creating a land corridor through southern Ukraine then such an annexation becomes much more likely, given the relative ease with which Russia would be able to project military force – and therefore power – through occupied territory and towards Moldova.

Any moves to change the existing political system of Transnistria, or include it in efforts to unite territories under Russkiy Mir, would certainly result in instability and the resumption of conflict within Transnistria and Moldova. Any such move towards formal annexation of the territory by Russia however would not manifest unforeseen. Instead, they would be preceded by extensive information operations and an announcement from the Transnistrian authorities of some form of referendum on whether Transnistria should join with Russia. It is likely that the Russian authorities may telegraph such intentions through statements, and indeed on 22 April Russian Brigadier General Rustam Minnekayev, acting commander of Russia’s Central Military District, stated that during the second phase of the “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine there would be efforts to “exit” into Transnistria.

On 25 April, unconfirmed reports suggested that several explosions had occurred in Tiraspol, Transnistria, near to the headquarters of the State Security Committee (MGB). Images from the site showed emergency services on-scene and two discarded weapon systems, most likely rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) variants. The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence was quick to label the incident as a ‘planned provocation’ by Russia, with Russia yet to officially comment. Then, on the morning of 26 April, further unconfirmed reports suggested than an explosion of unknown origin had occurred at a TV/radio centre in Mayak, Transnistria, which had reportedly been used to broadcast pro-Russian media. As with the first incident, there has been no official comment, although it is clear that Russia is likely escalating its actions in Transnistria. In response to the incidents, the President of Moldova convened a meeting of the Supreme Security Council to discuss the ongoing situation in the breakaway region. Transnistrian officials have accused Ukraine of attempting to spread the conflict into the region, and have imposed a 15-day ‘red’ terror alert level. Depending on the extent and severity of any Western responses to these incidents, Russia may seek to deploy forces to Tiraspol in the short term under the pretext of establishing security. Already, Russian forces have set the conditions for amphibious landings south of Transnistria by destroying a crucial bridge linking the area with Ukrainian forces deployed in Odessa. Any such Russian deployment to Transnistria would represent a significant escalation and a considerable challenge for the international community, given that the EU and NATO have no jurisdiction in the country.

As a result of fears around Russian and Transnistrian intentions regarding the breakaway territory, and the realisation that Moldova with a standing army of around 6,000 is not covered by any wider multilateral defence treaties or political organisations, Moldova has applied to join the EU. It is unlikely that Moldova will seek to join NATO in the short to medium term however, as neutrality is enshrined into its constitution. Meanwhile, on 16 March the Council of Europe officially adopted a resolution which states that the breakaway territory of Transnistria is Moldovan territory which is occupied by Russia. This resolution was adopted unanimously after Russia was excluded from the Council because of the Ukrainian invasion. Alongside the application to join the EU, the Ukraine invasion has also seen an upsurge in support for a potential reunification with Romania. Moldova was formerly part of Romania and reunification has often been floated at various points as a long-term policy goal of both Romanian and Moldovan politicians. Unification naturally would face hurdles. These would include the issue of Transnistria, which initially broke away in protest against proposals for Romanian-Moldovan unification. Yet, crucially, reunification would see Moldova automatically become part of the EU and reside under the protective NATO article 5 umbrella.

Central Asia

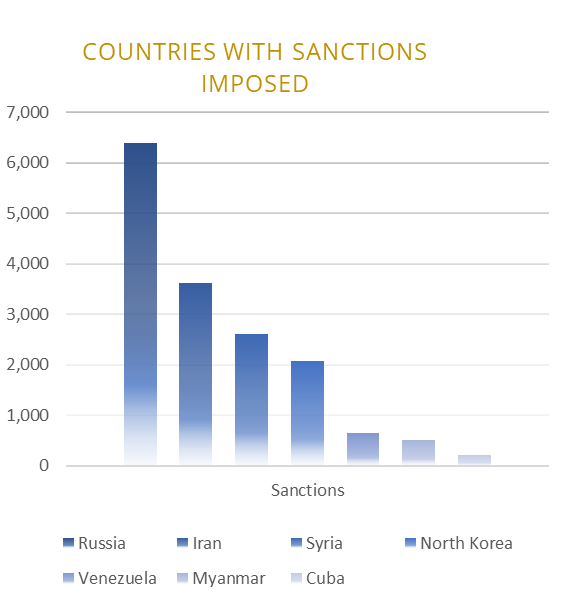

As a result of the war in Ukraine, Russia has become the world’s most sanctioned country – as can be seen in figure 3 below. At the time of writing, the country has been placed under at least 6,400 different sanctions. Many of these sanctions directly target the Russian economy and as a result this has seen a sudden and sharp contraction in its performance. It is estimated that over the course of the remainder of 2022 the Russian economy is likely to contract by fifteen percent, the largest contraction the country has experienced since the collapse of the USSR in the early 1990s.

This economic collapse is likely to lead to significant economic turmoil and possible civil unrest across Central Asia, in addition to Russia itself. This is because a number of states in Central Asia remain heavily dependent on the Russian economy either through trading relations, or more importantly, through the flow of remittances from migrant workers in Russia. Indeed, because of Russia’s economic downturn and the fall in the value of the Ruble, remittances to Central Asia are now expected to decline by twenty-five percent. Originally, they were expected to increase throughout 2022 as the world continued to recover from the worst economic shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic.

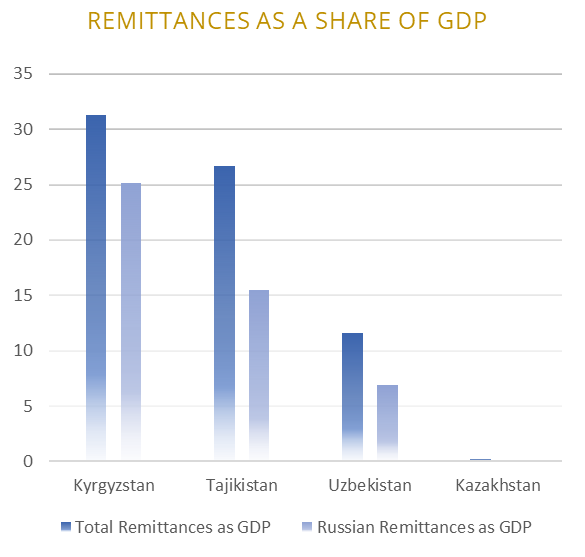

Central Asia as a whole is heavily dependent on remittances from migrant workers in Russia. The three Central Asian republics of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan sent 7.8 million workers to Russia in 2021. In return, these millions of migrant workers send remittances which make up significant contributions to the GDP of these states. Kyrgyzstan is the country most dependent on Russian remittances in the region, and it stands to see remittances decline by thirty-three percent in the wake of the Ukrainian invasion. Tajikistan is predicted to see a decline of twenty-two percent, whilst in Uzbekistan the decline is forecast to be twenty-one percent. Figure 4 below shows how dependent on remittances overall selected nations in Central Asia are, whilst also showing the contribution Russian remittances provide to respective GDP.

Kazakhstan is due to be the least affected by the fall in remittances from Russia as remittances play a small role in its economy, which is heavily oil based. Despite this, the nation is still expected to see a fall in remittances of around seventeen percent. However, the impact will be less significant than in other countries in the region as remittances, of which fifty-one percent come from Russia, are a much smaller percent of GDP. In the oil rich economy of Kazakhstan, total remittances make up only 0.2 percent of GDP.

Aside from remittances, all countries in the region are economically intertwined with Russia. Twenty-one percent of Kazakhstan’s trade and seventeen percent of Uzbekistan’s trade is with Russia, whilst Kazakhstan exports two-thirds of its oil supplies through Russian ports and onto global markets. Kazakhstan alongside the Kyrgyz Republic are both members of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

This encourages the free trade and flow of goods between constituent members which also include Armenia, Belarus, and Russia. As a result of this, both Kazakh and Kyrgyz manufacturing is tightly bound to the Russian economy and supply chains. This membership is likely to mean that both these countries will be under pressure by the EEU and Russia to maintain their EEU obligations to help mitigate the impact of the sanctions on Russia and their adverse second-order effects on other members of the EEU, whilst as Russian supply chains and imports are disrupted due to sanctions, this in time will filter through to other EEU nations.

Already Ernis Asanov, head of the Kyrgyz Pharmaceutical Union, has noted that sixty percent of all medical supplies in the country come through Russia. As pharmaceutical companies stop supplying Russia in compliance with sanctions, or find it harder to do so, this will lead to the cessation of exports to countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan by Russian manufacturers as they prioritise supplying the Russian domestic market. In time this will very likely lead to shortages of medicines and equipment in these second order markets, unless Central Asian states can rapidly diversify their supply.

Meanwhile, as Russia increasingly becomes a less attractive location for workers to travel to, many Central Asian nations will see their unemployment rates rise, as workers, many of whom are young males, may remain at home rather than travelling to work in Russia. This will place further strain on fragile public services – which will also be strained due to economic downturn.

In sum, the region is likely to face rising unemployment amongst young males, economic contraction, falling living standards and increasing strain on public services. These are all factors which lead to outbreaks of civil unrest and protests. Already in 2022, the region has seen one outbreak of large-scale civil unrest, in Kazakhstan. This left over 200 people dead and was only brought to a stop through Russian intervention. This intervention may incidentally further mean that the Kazakh regime is only more beholden to Russia than it was six months ago. Given that, regionally, conditions have only deteriorated since this unrest means that as the impact of invasion begins to be felt across Central Asia, political instability and further instances of civil unrest are highly likely to occur once more. Longer term, the invasion and the disruption it causes in the region is likely to only weaken Russia’s hold in the region, vis-a-vis China.

Already before the invasion, despite the existence of the EEU and long-standing historical ties, China had displaced Russia as the region’s largest economic player. Russia–Central Asia trade currently stands at around USD 18.6 billion, around two-thirds of China’s, and is far smaller than its value in the 1990s when it accounted for eighty percent of the region’s trade (USD 110 billion). As Russia’s economy declines under the weight of sanctions, China’s trade with the region will only increase. The economic shock produced in the region because of the invasion may result in a more assertive China, which has typically used finance and economics as strategic power levers. Beijing holds over forty percent of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan’s national debts and if the region sees an economic decline brought about due to the second order impacts of the Ukraine war, China may use this to try and wrest further economic or security concessions out of the region in exchange perhaps for debt alleviation, restructuring or an economic assistance programme.

Caucasia

Caucasia as a region contains two breakaway regions, both in the country of Georgia, which are heavily backed by Russia. These are South Ossetia, also known as the State of Alania, and Abkhazia, also known as the Republic of Abkhazia. The region is also home to the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, which contains the breakaway Republic of Artsakh. The location of these regions can be seen in Figure 5 below. Russia backs the two breakaway territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia; however, Russia has not recognised the Republic of Artsakh as it is disputed between two of its allies, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, states in the region which in recent years have tended to fall in line with Russia have all abstained or voted against Russia in recent UN resolutions. For the states in the region, in particular those which are home to breakaway Russian-backed territories, the invasion of Ukraine can be seen as an alarming escalation, whilst for Georgia in particular, it revives memories of the 2008 Russo-Georgia war.

The 2008 recognition of South Ossetia and Abkhazia by Russia came after the 2008 Russo-Georgia war. Since then, the republics have been recognised by each other and a number of states aligned to Russia such as Venezuela, Syria, and Nicaragua. Alongside this, they have also been recognised by other Russian backed breakaway territories such as Transnistria, Artsakh, Donetsk, and Luhansk. The two territories between them make up around twenty percent of Georgia’s territory.

Georgia maintains that both regions are under military occupation by Russia. One of the primary drivers for the Russo- Georgia war was the fact that Georgia was widely praised for successfully consolidating a transparent and democratic political system with a free and competitive economy. This stands in visible contrast to the Russian system across the border, which many perceive to be neither transparent nor truly democratic. A similar fear with regards to Ukraine’s trajectory since the 2014 Euromaidan revolution is believed to have partially led to the invasion of Ukraine.

On 31 March, the leader of South Ossetia, Anatoly Bibilov, stated the de-facto independent territory was looking to hold a referendum on whether it should unify with Russia. Initially this referendum was due to take place in 2014, however after the annexation of the Crimea, it was postponed over fears that it may result in further destabilisation in the post-soviet space.

Most of the residents of the territory have been granted Russian citizenship, whilst the territory is majority Russian speaking and is economically integrated with the Russian Republic of North Ossetia–Alania. As a result, plus the fact that the security of the breakaway republic such as it exists is underwritten by Russia, it is almost certain that such a referendum would see the territory vote to join Russia. The announcement from the President of South Ossetia that they wish to hold this referendum on joining Russia, resulted in the Georgian foreign Minister David Zalkaliani stating such a wish was “unacceptable,” and it would have “no legal force” as South Ossetia is an “occupied territory” that belongs to Georgia.

Much as in South Ossetia, Abkhazia is dependent on Russia for its security and much of its economy is linked to that of Russia’s. However, because Abkhazia culturally is home to a distinct ethnic group with their own language and script, there is much less desire in Abkhazia to become a part of the Russian federation. Indeed, in the wake of the announcement from the South Ossetian President about seeking a referendum to join Russia, the speaker of the Abkhazian parliament stated that “we have no intention of joining the Russian Federation.” Indeed, historically the Abkhazian elite have been more forthright in their attempts to create an independent state which is distinct from both Georgia and Russia, than their counterparts in South Ossetia who have always sought unification with Russia. This can be seen throughout Abkhazia’s recent past, such as when Abkhazia rejected the 2014 “integration treaty” with Russia, a treaty to which South Ossetia agreed. The war in Ukraine then has resulted in further destabilisation in this already unstable part of the world. As a result of the war, in March 2022 Georgia, alongside Moldova, formally applied for EU membership. It is believed that the Georgian government was placed under pressure from civil society and the mass pro-Ukraine/pro-EU protests which erupted across the country in the wake of the Invasion. Much as in Moldova there is the belief that joining the EU may help to restore some security to the country, which continues to be troubled by the Russian occupation of the breakaway territories. This is because whilst EU membership does not guarantee NATO membership, the EU has its own mutual defence clause. Clause 42(7) of the EU Lisbon Treaty states that if an EU country is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other EU countries have a binding obligation to aid and assist it by all the means in their power, in accordance with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter and the commitments of those countries which are NATO members. This clause also states that it does not affect the neutrality of EU states with a policy of neutrality. As a result of this clause, belonging to the EU would guarantee a baseline of security membership – whilst the granting of EU membership is also seen by many in non-NATO states as part of the path towards eventual NATO membership.

This Russian presence in Georgia, which is comparable to other countries with Russian-backed breakaway territories, has been described as ‘occupation without occupation’. Effectively, the separatist regions become strongholds from which Russia can intimidate and destabilise the states that once administered them, whilst they can also set the conditions for an insidious physical occupation to take place. In this way, Russia can threaten swift occupation of much of the wider country, whilst influencing the actions of the wider state, all at a much cheaper and flexible cost than a traditional occupation.

Whilst both breakaway territories have supported Russian actions in Ukraine, and South Ossetia is using the instability to try and once again join Russia, there is the possibility that because of economic sanctions on Russia, positive sentiments in both territories towards Russia may begin to dissipate. This is because Russia has announced that it is cutting the size of the subsidies it gives to both territories to help support them. In the announcement, it was stated that both territories should within three years no longer be financially dependent on Russia. Given that at the time of writing around fifty percent of the budget for both territories comes from Russia, both territories are likely to see profound economic problems in the coming years.

The repercussions of the invasion in Ukraine are also being felt in the Nagorno-Karabakh region, also known as the Republic of Artsakh. The region erupted into war in 2020 and as Russia has good relations with both Armenia and Azerbaijan, Russia ended up becoming a guarantor of the eventual ceasefire treaty. As a result, 2,000 Russian peacekeepers deployed to police the frontline between the two sides. Since then, the region has been relatively peaceful, however recent weeks have seen an escalation in hostilities as Azerbaijan, backed by its ally Turkey, took advantage of rumours that Russian peacekeeping troops were leaving for Ukraine, to occupy the village of Farrukh. Historically, insecurity in Nagorno-Karabakh has flared up whenever Russia has appeared weak or distracted.

Alongside this, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is also likely to lead to the gradual marginalisation and delegitimization of the Russian peacekeeping mission in Nagorno-Karabakh. Since the end of the 2020 war, Russian peacekeeping troops have maintained the balance of power – which had tipped in favour of Azerbaijan through its alliance with Turkey. Prior to this, historically since the end of the first war in the 1990s there had been minor change in the balance of power in the region. A delegitimization of the Russian peacekeeping forces in the region may well only further lead to a cycle of escalating hostilities as it would once more shift the balance of power in favour of Azerbaijan.

More widely in Armenia, the Ukrainian war has led to fears that Russia may once again seek to integrate Armenia further into the “Union State” which already exists between Russia and Belarus. Already Russia and Armenia cooperate within the CSTO, and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), whilst a further 250 bilateral treaties of friendship, cooperation or mutual assistance exist between the two states. The fear of further integration was heightened in February 2022 when the President of Belarus, Aleksandr Lukashenko, stated that “Armenia can’t escape it”.

To try and keep a point of differentiation between Armenia and Russia, Armenia has declared neutrality on the subject of Ukraine and abstained in the UN resolution condemning the Ukraine invasion. Two days later a phone call took place between the Foreign Ministers of Armenia and Russia where “coordinating approaches in the international arena” was discussed.

In the caucus region then, the invasion of Ukraine has prompted Georgia to seek EU membership whilst in the Georgian breakaway territories it has prompted one to seek accession into Russia. If this referendum does indeed take place, then it will only lead to further destabilisation in the region. Despite the prospect of destabilisation, the President of Georgia, Salome Zourabichvili, has ruled out the prospect of war – stating that Georgia would not try to bring the breakaway territories back by war as this solves nothing. Meanwhile, the news that Russia is to effectively cease economic support over the next three years to the breakaway territories of Georgia is over time also likely to generate increased instability in the region. Perversely, for South Ossetia, the news that such economic support is to be dismantled may only increase their determination to become an integral part of Russia – as then such economic support will be guaranteed.

Conclusion

Across the Russian periphery the war in Ukraine has had several impacts all of which are likely to play out over the medium to long term. These impacts range from the prospect of further conflict in the caucuses, the rise of Chinese power across Central Asia, and the expansion of both NATO and theoretically the EU – ironically two institutions that Russia invaded Ukraine to try and prevent expanding.

The war in Ukraine can be seen perhaps as a proxy war in what is shaping up to be the 21st century’s contest of ideas – that between liberal democracy and authoritarianism. Russia and China, both authoritarian states, pledged to stand together in February against western and liberal forces. Within this framework of the Ukrainian war being part of a contest of ideologies, the most instantaneous and sizeable impacts of the war from a western perspective are likely to be the announcements that states on the periphery wish to join western institutions which uphold those western values.

There is now the almost certain accession to NATO of Finland, and probably Sweden. Both nations have historically worked closely with NATO without ever explicitly giving up their neutrality. As outlined, their accession would further entrench NATO security around the Baltic and the Gulf of Finland, providing additional reassurance to NATO’s Baltic members. It would also mean that NATO borders stretched across a strategic part of Russia, and whilst Russia can issue hostile warnings – it seems at the current time there is little it may be able to do to stop this accession from occurring.

Alongside this expansion of NATO is that Moldova and Georgia have hastened their applications to join the EU. This should be seen as positive by the West for it shows that within the contest between liberal democracy and authoritarianism, states and citizens which once suffered under the latter continue to aspire to the former. The fact that these two nations have decided that western and liberal values are where their futures lie should be welcomed. In the case of Georgia, the country paid the price in 2008 that Ukraine is now paying in 2022 for wishing to aspire to these values. As a result, an outright rejection of these two applications is unlikely – both may well be granted candidacy status within the next few months. We can also expect Ukraine’s EU membership application to also likely result in candidate status being granted.

Within the same vein, the societal transformation in Bulgaria when it comes to Russia and the realisation of how much influence Russia has over the Bulgarian media and economy should also be welcomed, especially as the country is already a NATO and EU member. If this shift were not to take place, then the country would increasingly find itself at odds with its official allies and partners in NATO and the EU, and may come to be viewed as something akin to a Russian trojan horse within western institutions or alongside Hungary as an outlier state. Across the Baltics, governments will feel vindicated that the wariness they had with regards to Russia has been broadly realised. Whilst NATO is making efforts to help secure the Baltics, there needs to be a focus on how best to deal with the Russian language disinformation in the region without marginalising Russian speakers. The fact that NATO more widely now shares their viewpoint with regards to Russia will only serve to bolster Baltic efforts to inoculate themselves against threats such as Russian unconventional warfare. Given that the region is likely to be a key battleground between Russia and NATO, it is likely that over the coming years the region will see heavy investment from NATO and the west – not just in conventional

deterrence, but also perhaps in unconventional deterrence. Estonia’s state-run Russian language TV channel for instance may be emulated – and further outreach to the region’s Russian speaking minorities is likely to take place.

In Central Asia, where economies are closely intertwined with Russia’s, the main impact will be felt economically at least initially. However, economic disruption, especially in authoritarian states, often leads to civil unrest and protests. The region is already volatile, as demonstrated by the eruption of widespread protests in Kazakhstan earlier in the year, as such it is likely that the region’s states will see an uptick in civil unrest and protests movements. Further to this, China may take the opportunity to further cement its influence in the region, whilst Russia is distracted by the war in Ukraine. Such moves may over time lead to friction between China and Russia and undermine the newly signed friendship agreement between the two states – particularly as Central Asia has historically been seen as Russia’s traditional sphere of influence.

Central Asian nations will not be the only states on the Russian periphery to suffer economic fallout from the Russian invasion of Ukraine – across the Russian-backed separatist territories, all are likely to suffer. South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria are all economically dependent on Russia and the announcement that the former two will cease to receive funding in three years will be greeted with trepidation. This announcement is likely to further drive South Ossetia and Transnistria to seek to become integral parts of Russia – a scenario more likely for South Ossetia due to favourable geography. However, if Russia were to successfully create a land corridor in southern Ukraine then subsequent moves to annex Transnistria should not be ruled out. All these scenarios would naturally see tensions in the respective regions rising and would mean that the outbreak of hostilities could once again occur.

Finally, there is the disputed region of Nagorno Karabakh where Russia plays a stabilising role. If Russian peacekeeping troops are moved out of the region to Ukraine this will alter the balance of power and may mean that the escalation in hostilities already noted continues. Alongside this, as the Ukraine invasion serves to delegitimise the Russian army in the eyes of many, longer term this could also lead the parties involved in the conflict to simply disregard the presence of Russian peacekeepers and this too would then lead to an escalation in hostilities and potentially would see the region back in open conflict. For Armenia, which relies on Russian peacekeepers to keep the balance of power from tilting too far in the direction of Azerbaijan, there is the fear that the words of Lukashenko in February are true, and that over time they will see themselves once again subsumed into a wider Russian dominated union state – as such it should be expected that Armenia will seek to create daylight between itself and Russia where possible on policy and foreign affairs in the near future.

Overall, across the Russian periphery one thing that the war in Ukraine has done is create more uncertainty and tension. It has meant that states must choose between a liberal democratic alignment or closer ties with Russia. It has also upset the balance of power and the realpolitik which have allowed dormant conflicts to stay dormant and countries such as Finland to remain neutral throughout the Cold War. Depending on how the latest phase of the Russian invasion plays out is also key to what occurs on the Russian periphery – if Russia continues to see a succession of military failures in Ukraine, then the Kremlin may turn to “easier” wins elsewhere such as the annexation of South Ossetia, to help shore up domestic popular support. Overall though, the future for countries along the Russian periphery is one of uncertainty, of having to choose a “bloc” to align to, and for both states and unrecognised territories the future will present a more challenging economic environment which in turn could lead to upsurges in civil unrest, protests and popular discontent at rulers and governments.

Support for operations in Ukraine

Our team of risk management specialists and intelligence analysts, combined with on-the-ground security support from our global partner network can help secure your operations.

Learn more about how we can secure your operations