Evacuations from Israel and High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

East Africa: Desert locust infestation

17 Feb 2020

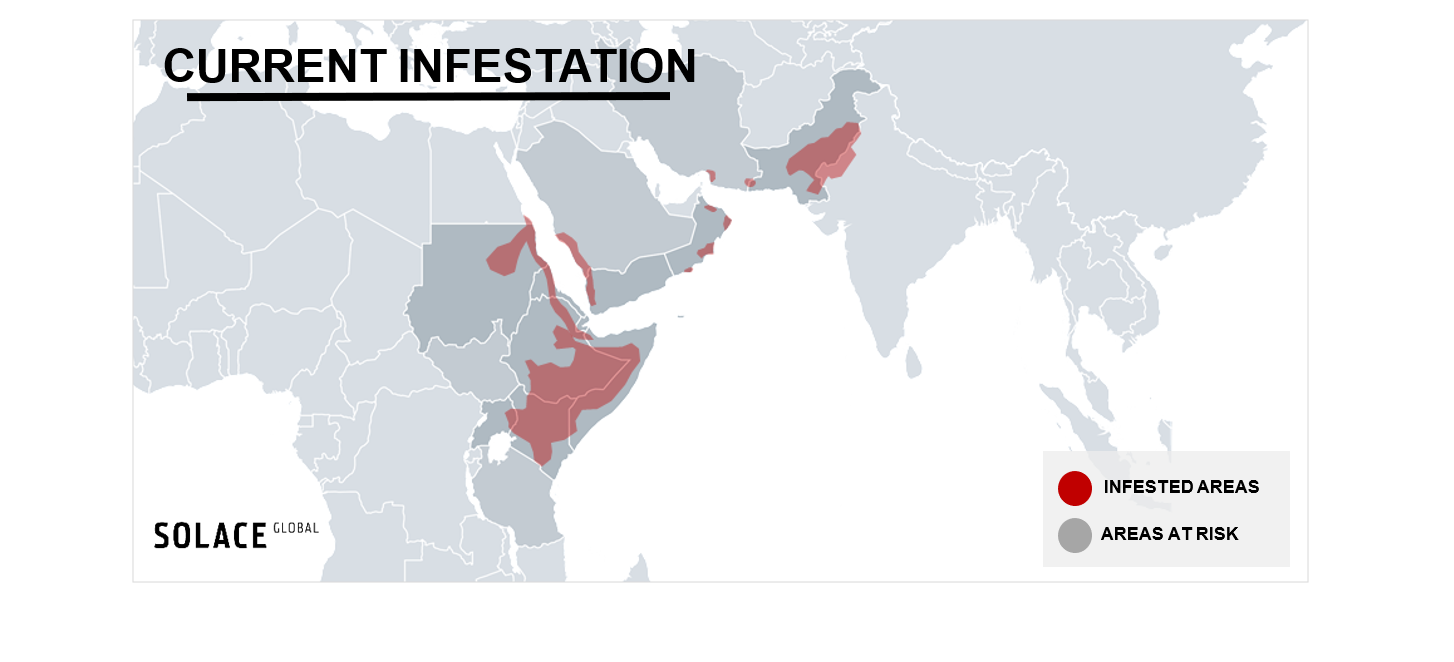

The biggest desert locust outbreak in almost three decades has been affecting large parts of East Africa, including Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan, Eritrea and Uganda.The locusts are severely threatening the food security in the region, devouring crops and destroying the livelihoods of entire communities of farmers and herders. Together with the growing risk of a humanitarian crisis, the emergency has the potential to cause a resurgence of inter-communal conflict, banditry and unrest.

Key Points

- Since October 2019, the biggest desert locust plague in almost three decades has been affecting large parts of East Africa, including Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan and Eritrea.

- The infestation has now reached Uganda and is threatening to expand into South Sudan and Tanzania. The rapidly expanding swarm has resisted all attempts to control it, while the absence of the rule of law in several regions has hindered government and international efforts.

- The locusts are severely threatening food security in the region, devouring crops and destroying the livelihoods of entire communities of farmers and herders.

- Together with the growing risk of a humanitarian crisis, the emergency has the potential to cause a resurgence of inter-communal conflict, banditry and unrest.

- Efforts to tackle the issue and its mid-to-long-term consequences will also put severe strain on governments’ resources and is likely to threaten the stability of governments throughout the region.

Desert locust infestation threatens livelihoods of the population

On 10 February, the Ugandan government announced the deployment of military personnel to aid in the fight against the locust swarm that has been recently sighted within the country. Hundreds of spraying devices have been distributed in the six affected districts to spread thousands of litres of chemical insecticide to attempt to restrict the insect’s expansion and manage the crisis ahead of the harvesting season.

The locusts have also crossed into Pakistan from Iran during the summer of 2019 and have grown exponentially since, forcing Prime Minister Imran Khan to declare a state of emergency on 1 February 2020. The Somalian government also declared a state of emergency the following day, seeking to gather funds and support ahead of the second wave of locusts, which are expected to effective way to tackle the issue is aerial spraying of insecticide, estimated to cost a total of 76 million USD. Only 20 million USD has so far been received, with a large part coming from the UN emergency fund.

The Locust Plague

This desert locust outbreak is estimated to be the largest and most destructive in the past 25 years and is currently affecting most of the East African sub-continent and parts of South Asia. While the insects do not represent a direct threat to human life, they destroy crops and pastures while feeding and breeding, threatening the food supply and livelihoods of millions of people in the region, where food security is already precarious.

The swarms, which currently contain an estimated total of 300 billion insects, can migrate 150km a day and eat the equivalent of their body weight in crops, roughly enough to feed 84 million people a day. In a region where the level of food insecurity is severe, the sudden loss of tens of thousands of acres of crops has the potential to trigger a large-scale humanitarian crisis and foster insurgency and unrest.

While not an uncommon phenomenon in the region, the size and growth of the infestation has been attributed to the heavy rains and the tropical cyclones that have hit the Horn of Africa in the past year. Initially migrating from conflict-ridden Yemen between October and November 2019, the swarms have rapidly multiplied in Somalia thanks to the flooding that occurred in November, the worst in the country’s history. The waters allowed vegetation to grow on the arid terrain, providing the perfect feeding and breeding conditions for the insects. The lack of governance throughout most of Somalia led to the authorities being unable to implement adequate emergency plans to tackle the outbreak.

The efforts to monitor and control the infestation initiated by the Somali government and neighbouring countries were ultimately frustrated by the landfall of Cyclone Pawan in December 2019 that overwhelmed the existing resources. With their capacity to multiply up to 20-fold in a month when uncontrolled, the swarm quickly spread to Kenya, Ethiopia, and to the Red Sea Plains in Eritrea and Sudan.

Having now crossed from Kenya into Uganda, the infestation is also threatening the neighbouring South Sudan and Tanzania, which have been put on a UN watchlist. The FAO Director General, Director-General Qu Dongyu, has continuously warned that, if the issue is not effectively tackled, it has the potential to spread across the continent and affect up to 30 countries, causing a large-scale humanitarian crisis. Fears that the situation might not be brought under control before April, when the long rain season will start, are growing. If not restrained, the swarms could grow 500 times before June, when the start of the dry season will effectively slow the breeding.

While not an uncommon phenomenon in the region, the size and growth of the infestation has been attributed to the heavy rains and the tropical cyclones that have hit the Horn of Africa in the past year. Initially migrating from conflict-ridden Yemen between October and November 2019, the swarms have rapidly multiplied in Somalia thanks to the flooding that occurred in November, the worst in the country’s history. The waters allowed vegetation to grow on the arid terrain, providing the perfect feeding and breeding conditions for the insects. The lack of governance throughout most of Somalia led to the authorities being unable to implement adequate emergency plans to tackle the outbreak.

The Underlying Causes

Climate change, combined with the inability from local governments to effectively tackle the outbreak, are largely to blame for the scale of the emergency. While desert locusts are commonly found in these areas, it was the atypical weather conditions that allowed it to rapidly multiply. The unusually frequent heavy rains and tropical storms of the past year have caused arid regions to flood and grow an exceptional amount of vegetation, providing the perfect ecological conditions for the locusts to prosper.

The repeated flooding of the last quarter of 2019 was also responsible for the destruction of large areas of farmland, infrastructure and roads, affecting over 2.8 million people across the Horn of Africa. This greatly depleted the governments’ already limited emergency management resources, leaving them unable to conduct comprehensive pest control operations before the locust outbreak became overwhelming.

Experts have also highlighted the fact that, due to the sporadic nature of outbreaks of this size, the resources and know-how dedicated to pest control tend to be given a lower priority compared to those committed to recurring and ongoing crises, such as droughts and violent insurgencies. Moreover, the aerial spraying operations necessary to tackle the locust outbreak, particularly at the start of the second wave of hatching, require a degree of intergovernmental coordination that is difficult to achieve in the region. These would require permission to operate across borders and to conduct comprehensive monitoring and control exercises to follow the swarms and tackle them at their early stage of development.

The weather extremes across the two sides of the Indian Ocean, which have caused an unprecedented bushfire season in Australia and large-scale flooding in East Africa, are the result of extreme fluctuation in the Indian Ocean dipole index. This refers to the difference in sea-surface temperatures across the Ocean, which is responsible for periods of heavy rain and heatwaves in the two continents. Like many other climate phenomena, the Indian Ocean dipole has been greatly affected by global warming and scientists have warned that such fluctuations will become more extreme and frequent. This will increase the number and severity of droughts, flooding and locust outbreaks in the entire sub-region, unless preventive measures are taken at a domestic and international level.

Consequences: Hunger, Instability and Violence

The locus plague represents a severe threat for local populations, many of whom make their living through farming, as it consumes both their produce and the forage for their livestock. The outbreak and its destabilising consequences are worsened by several pre-existing conditions in the affected regions, which are among the poorest, unstable and conflict-ridden in the world.

Food security. While the food security in East Africa has been precarious even in favourable times, the past years have seen a recurring cycle of droughts and flooding that has frustrated efforts to build a sustainable agricultural sector. According to UN estimates, at least 19 million people suffer from acute hunger across Somalia, South Sudan, Kenya and Ethiopia. Attempts to both improve food security and deliver aid, while ongoing, have been complicated by armed conflict, extreme weather and violent insurgency in the region. Last year’s tropical cyclones, which have caused severe damage to cultivated land and infrastructure, were also central in propelling the growth of locust outbreak and in worsening the risk of a widespread famine. While accurate data on agricultural losses is not yet available, several communities across Kenya and Ethiopia have reported 100 percent of their crops being destroyed by the swarms and these numbers are only expected to rise with the second wave of hatchings in March.

Food prices and criminality. A direct consequence of the steep decline of food supplies is a spike in the pricing, particularly when the government authorities do not possess the resources necessary to counter market fluctuations with subsidies. Reports indicate an increase of between 14 and 40 percent in the prices of basic crops, such as maize and beans in East Africa, while Pakistan has registered an inflation in the prices for tomatoes and wheat. Together with additional challenges to famine prevention, inflation in food prices also causes an increase in speculative criminality and hoarding of basic resources, further threatening stabilisation attempts by the government. By making primary goods unavailable to most of the population, food shortages and high prices often fuel criminality and banditry, particularly in most rural areas and societies structured on a tribal basis, where rule of law is harder to maintain.

Government instability and civil unrest. The outbreak also presents several risks on a political level, as the inability by the different governments to tackle the crisis is likely to fuel popular discontent, which has the potential to escalate in civil unrest. The likelihood of large-scale anti-government demonstrations is influenced by the ability of the authorities to effectively respond to these issues, securing adequate food supplies and compensation for those communities that suffered losses in cultivated land and pastures. More relatively stable governments, such as those in Kenya and Pakistan, are likely to face a significant degree of unrest caused by anger over their aggressive trade policies or broken campaign promises centred around food security.

Intercommunal violence. Conflict and violence, particularly on a regional and local level, are often directly linked to scarcity of primary resources. A relevant example of a conflict that will be affected by the loss of thousands of acres of crops is the one between sedentary farming communities and nomadic herders, which are known to clash over the control of land. While the bloodiest among these conflicts are in West Africa, countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania have seen a significant degree of inter-communal tensions and violence, which are likely to escalate as the crisis continues.