Evacuations from High-Risk Locations Call +44 (0)1202 308810 or Contact Us →

2023 Turkish Elections: Regional Implications

What Geopolitical Implications Lie Ahead for Turkey?

On 14 May 2023, Turkey will be holding a general election that will see the population elect both the President and 600 members of the Grand National Assembly – Turkey’s parliament. If no presidential candidate is elected with greater than 50 percent of the vote on 14 May, then a second round of voting takes place between the top two candidates. Turkey’s parliament will be elected via party-list proportional representation.

There is a lot at stake domestically for Turkey but the elections are also of global importance as the country is a key regional power. It is the only Muslim-majority member of NATO, boasts the world’s nineteenth largest economy, and in recent years it has used its political and military power to help shape outcomes across the Middle East and Caucus region. These elections have taken on further significance as Turkey’s dominant ruling party, Justice and Development (AKP), and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, face significant competition for the first time in two decades. A combination of factors has led to both the AKP and President Erdogan being the weakest they have been since the early 2000s. These factors can broadly be split into three themes: the mishandling of the Turkish economy, rising authoritarianism, and criticism of the post-earthquake response in February 2023.

Meanwhile, the opposition is broadly united behind one candidate. Kemal Kilicdaroglu is the nominated candidate for the National Alliance (NATION), a coalition of six opposition political parties. The unification of these parties aims solely to oust Erdogan, essentially by making the elections a binary choice. This unity however is fragile, and cracks have already begun to appear. By the deadline to register, two additional presidential candidates had also made it onto the ballot; Muharrem Ince and Sinan Ogan.

How Erdogan Came to Presidential Power

The last two decades in Turkish politics have been dominated by President Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP). Turkey had experienced a period of sustained economic growth and political stability for the majority of their premiership, however, in recent years their popularity has begun to wane.

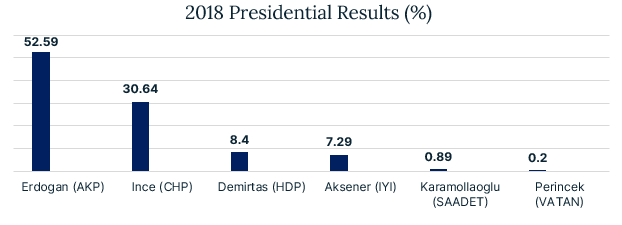

The last general election took place in 2018, which were the first under a new presidential system established after Turkey’s 2017 constitutional referendum and following the failed coup d’état in July 2016. President Erdogan retained the presidency and inherited new powers the position had been bestowed with under the reforms. However, the AKP lost its parliamentary majority and had to enter a coalition with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). Since then, the largest opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), has won the mayoral elections in Turkey’s three biggest cities: Ankara, Istanbul and Izmir.

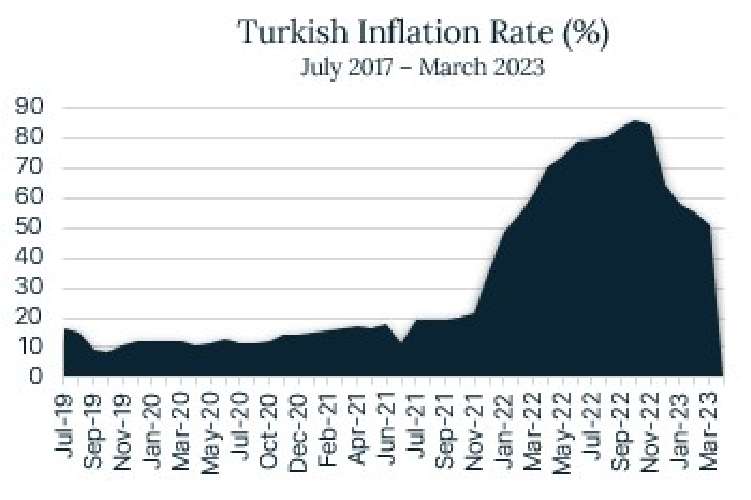

The AKP has traditionally relied on its record of economic growth to win elections, but the upcoming vote takes place amid widespread criticism of Erdogan and the AKP’s mishandling of the Turkish economy, founded in the several financial crises that have hit the country. Since the 2018 election, inflation has at times risen out of control, peaking at 85.51 percent in October 2022. Whilst falling since then, inflation still stood at 50.51 percent in March 2023. Concurrently, the value of the Turkish Lira has collapsed, losing 30 percent of its value against the United States Dollar (USD) in 2022, having lost 44 percent in 2021. This all contributed to rising borrowing costs and correspondingly increased rates of loan defaults across the country.

Accusations of Corruption and Authoritarianism Against Erdogan

Allegations of corruption and authoritarianism have also been major issues leading up to the 2023 presidential election, with Erdogan and the AKP being accused of corruption, nepotism, and undermining democratic institutions. There are also lingering repercussions to the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which many Turks criticised.

Further, Erdogan has consolidated his power, with critics accusing him of taking steps to establish a de facto one-party state, cracking down on dissenting voices and arresting opposition leaders. This has continued even into the campaign, with Turkish police in April 2023, detaining 110 people, including politicians, lawyers, and journalists over alleged militant ties; the majority of those arrested were Kurdish activists and members of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP).

The government has also used emergency laws to restrict civil liberties, whilst Erdogan has also been actively suppressing media freedoms and journalists. The country’s ranking on the Press Freedom Index has declined sharply in recent years, and many journalists have been imprisoned for their reporting. These factors have contributed to a growing sense of dissatisfaction and disillusionment among many Turkish citizens and the election presents an opportunity for democratically minded voters to potentially remove Erdogan.

Erdogan Confidence Waning After Turkey Earthquakes

These elections also follow the devastating February 2023 earthquakes which killed at least 50,000 people in Turkey and left millions homeless.

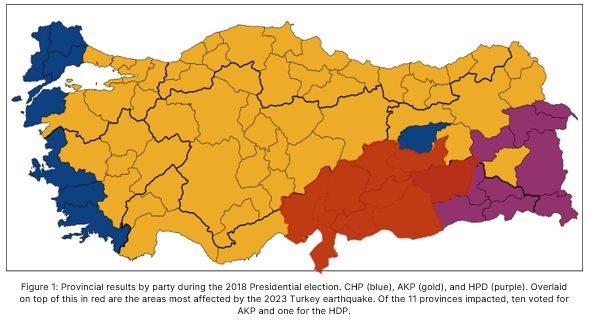

The worst of the devastation occurred in regions which were strongly pro-Erdogan, although both Erdogan and the AKP have been extensively criticised for their response to the disaster and indeed their readiness for such eventualities. Funding for the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD) had been reduced by 33 percent in the 2023 national budget. Moreover, many of the newer, supposedly earthquake-proof, buildings collapsed.

A significant number of these had been declared unsafe and unlawful until Erdogan himself intervened in 2018 and pushed through an amnesty legalising the status of thousands of buildings that had been illegally built without proper documentation and inspections. The earthquake has also brought to light allegations that the AKP has misused the country’s earthquake tax fund, which was implemented in the wake of the 1999 Izmit earthquake, for non-earthquake-related spending. This combination of factors have led to widespread anger and disillusionment with the government, and many believe that the earthquake could be the catalyst for significant political changes in Turkey, much like the 1999 earthquake was.

1.5 M

Survivors Living in Tents

46,000

Survivors in Container Houses

Key Opponents to Erdogan

The threat to Erdogan and the AKP’s dominance has also increased as the country’s long-divided opposition has broadly united behind one presidential candidate, Kemal Kilicdaroglu. Kilicdaroglu is the leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the chosen nominee of the National Alliance (NATION), a coalition of six opposition parties contesting both the presidential and parliamentary elections.

Further to this, whilst not participating in the Nation Alliance, Turkey’s Kurdish parties have stated they will not stand any presidential candidates, effectively meaning the choice is between Erdogan or Kilicdaroglu. There are two other presidential candidates standing, Muharrem Ince of the Homeland Party and Sinan Ogan of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party. The greatest threat to a united opposition is Ince, who is currently polling at between three and seven percent.

Possible Outcomes From Turkey Elections

Implications for Minorities in Turkey

Domestically, one area that this election will influence is the Turkish government’s policies towards ethnic minorities, in particular the Kurdish population. However, it will also likely inform how pluralistic and tolerant the country’s body politic may be more widely towards other minorities such as the Alevi.

Under Erdogan in the early 2000s, the Turkish government reduced the levels of state repression against Turkey’s Kurdish minority and reversed restrictions on the use of the Kurdish language. This was all part of a lengthy peace process with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). This peace process however collapsed in July 2015. Since then, Erdogan, in tandem with his allies the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), has once again presided over a resurgent crackdown on the Kurdish minority.

If Erdogan secures re-election in May, then it is highly likely that this crackdown will continue. This likelihood would increase if Erdogan only retains power through the support of the MHP, which is staunchly against any concessions by the Turkish state to its minorities.

What Will Happen for Minorities if Erdogan Loses the Election?

However, in the event that Erdogan loses, Kurds and other minorities in the country will likely benefit from an easing of sociocultural restrictions. Since 2015, the CHP, the main opposition party to Erdogan’s AKP, has built bridges with the Kurdish minority. Indeed, since March 2022 the CHP has promised that they would bring peace to the Kurds if they returned to power. This was stated in a speech made by Kemal Kilicdaroglu, where he also acknowledged that the Kurds have “suffered a lot”. Further bolstering this assessment is the fact that Kilicdaroglu himself belongs to one of the country’s long-discriminated religious minorities, the Alevi.

In April 2023, Kilicdaroglu made a short video on Twitter which was seen over 100 million times, where he stated that he was an Alevi. Whilst this was already known, Kilicdaroglu had often avoided speaking about this publicly. However, in broaching this directly, he has now raised awareness around the issue of ethnic or religious identities in Turkey. Historically, Turkish politicians have sought to dissociate themselves from their religious or ethnic minority backgrounds. Famously, former Prime Minister Turgut Ozal was a Kurd, although he never publicly acknowledged this. Given the fact that Kilicdaroglu has brought his identity into the open and has also initiated conversations and agreements with the Kurds, it is almost certain that any Kilicdaroglu government will seek to foster a more politically and religiously tolerant Turkey.

Economic Implications For Turkey

In the wake of this election, the Turkish economy is almost certain to see immediate changes in policy. Initially, under Erdogan’s first decade in power, the Turkish economy performed very well and between 2003 and 2013, Turkish GDP per capita rose from USD 3,600 to around USD 12,600. However, it has subsequently declined to around USD 7,340. Alongside this GDP decline, the unorthodox fiscal policies under Erdogan have further undermined the economy. Since around 2010, the country has artificially kept interest rates low. This has resulted in a severe depreciation of Turkish Lira on international markets, and surging inflation. Since 2018, the depreciation of the lira and the country’s inflation rate have both become increasingly noticeable.

Alongside this, the independence of the country’s central bank has over time become eroded, with Erdogan “advising” the central bank on operational and policy matters, and firing policy officials, including three governors at the institution who have disagreed with him. Such displays of political interference in what should be an apolitical institution have seriously damaged the international credibility of the country’s central bank. Erdogan’s economic model, such as it exists, was designed to try and deliver large amounts of investment, a strong lira, a current account surplus, and price stability. Instead, it has brought the direct opposite in all four cases.

Possible Economic Outcomes if Erdogan Loses the Election

The opposition has already stated that if they were to win, they would return Turkey to conventional economic policies. This would almost certainly portend efforts to rebuild the international credibility and apolitical nature of the country’s central bank. It would also likely result in interest rates increases from their current level of 8.5 percent, since conventional economic policy suggests that higher interest rates restrict the supply of money in an economy and thus help to combat inflation. For context, the monthly inflation rate in March 2023 was 50.5 percent, with the annual 2023 inflation rate predicted to be 41 percent, as opposed to the forecasted 22 percent. National Alliance have promised that under their conventional fiscal policy, they would push inflation back into single digits within two years.

Whilst the most sweeping economic reforms will be enacted by the opposition, even the AKP has begun to admit they will have to address the country’s poor economic performance if they secure victory. Indeed, the AKP also committed to lowering inflation to single digits and reducing unemployment to seven percent in their April 2023 manifesto. Further evidence of a possible post-election shift in AKP economic policy includes their decision to approach the former deputy prime minister in charge of the economy, Mehmet Simsek, to help the party “overhaul economic policy”. However, Simsek reputedly refused to help the AKP rebuild its economic policy. As such, despite the manifesto promises, there currently remains little credible substance behind the promises from the AKP that they would return to conventional economic policy.

As such, regardless of which presidential candidate wins, a reorientation of the Turkish economy is almost certain to occur. This will likely presage higher interest rates and a further devaluation of the Turkish Lira. In the short term, these will only lead to a tightening of economic restrictions, however over the medium to longer term they will allow for a much-needed rebalancing of the Turkish economy.

Turkey Election Results and Earthquake Reconstruction

In the aftermath of the February 2023 earthquakes, both the AKP and the National Alliance have promised to rebuild the worst affected areas of the country. The AKP manifesto promises to build a total of 650,000 new houses, 319,000 of which they claim will be constructed in 12 months. Alongside this, they also claim that they will create a national risk shield model, which would allow 81 Turkish provinces to create “disaster resilient cities”. However, the AKP’s claims regarding earthquake rebuilding will almost certainly be undermined by their actions during the last two decades in government. This has seen the government allow capital collected under an “earthquake tax”, originally implemented following the 1999 earthquakes, to fund public infrastructure development such as roads and railways, rather than as originally intended as a ring-fenced endowment for post-earthquake reconstruction or the earthquake-proofing of buildings.

Further to this, the AKP-led government also allowed repeated amnesties for illegally-built apartments, many of which were constructed without meeting the country’s earthquake-proofing codes and regulations, whilst many other apartments officially designed as being “earthquake resistant” still collapsed due to corrupt building and permit processes. The National Alliance has pointed out that these processes, and many other related issues, marred the government’s initial response to the earthquake. Naturally, they have also promised to press on with rebuilding the country’s damaged cities, however, they are girding their rebuilding proposals around the theme of trust. They have repeatedly stated that the AKP cannot be trusted to follow through on its promises, and that even if they did, many citizens would still be uncertain as to the standards and quality of reconstruction.

This forthcoming election is not the first time that an earthquake and the country’s initial response have potentially played a significant role. Indeed, the official response to the powerful 1999 Izmit earthquake, which killed around 17,000 people, was a major factor in the collapse of the then-ruling government’s popularity, and directly led to the rise in support for AKP which first brought the party, and Erdogan, to power. An interesting dynamic relating to the earthquake is the fact that as figure 1 below illustrates, it primarily impacted provinces which have traditionally been considered AKP strongholds. As such, public outcry at the poor response from the government is likely to generate an outsized electoral outcome in these regions.

It should be noted however, that regardless of which candidate is elected, there is unlikely to be much difference in terms of the speed and efforts of rebuilding. The estimated total cost for rebuilding could reach around USD 100 billion, equivalent to around 11 percent of the country’s total GDP in 2022. The major differences will likely include both international and domestic faith and trust in the rebuilding processes.

Opportunity for Political Reform in Turkey

A final major domestic issue in this election will be the process of political reform. Since Erdogan came to power, and particularly since the failed 2016 coup d’état, Turkey has become an increasingly authoritarian state. The AKP and Erdogan have successfully consolidated power through constitutional changes and by imprisoning opponents and critics.

Their success in consolidating power can be demonstrated by the fact that since first coming to power in 2002, Erdogan and the AKP have consecutively won 13 elections, and three referendums, and survived the coup attempt. The 2017 referendum, which approved several constitutional amendments proposed by the AKP, transformed Turkey from its historical parliamentary system of government, as founded by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk in 1923, into a government with an executive presidency. Such a transformation had been a goal of both Erdogan and the AKP since at least 2005. Critics of Erdogan have stated that since he and the AKP first came to power they have slowly and methodically destroyed the founding ideals of the Turkish Republic as set out by Ataturk.

What Political Changes Could be Expected if National Alliance Win?

Given the changes that have occurred under AKP rule, the National Alliance have stated that they would seek to roll back many of the policies and reforms of the last two decades. This includes returning the country to a parliamentary system and re-establishing the role of Prime Minister. They would strengthen the role of parliament, for instance by enshrining in the Turkish constitution its authority to back out of international agreements, and would give it more power in fiscal and financial matters. They also pledge to turn the position of president into an impartial role with no political responsibility, which would strip the office of its right to issue legislative vetoes and decrees. Furthermore, any future president would have to sever ties to any political party, could only serve one seven-year term and afterwards would be banned from participating in active politics.

As a result of this policy platform around domestic reforms, these elections will be seen by many as an effective referendum on whether to continue with the increasingly authoritarian and centralised rule of Erdogan and the AKP or whether to return the country to a system closer to that which was founded by Ataturk.

Wider Geopolitical Implications for Turkey

The outcome of the general election will not only affect Turkey’s internal affairs but will also impact the country’s foreign policy, having significant implications in the fields of regional and international diplomacy and security. President Erdogan and main opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu will likely adopt different policy positions on a number of issues and whoever is elected stands to define Ankara’s stance on the European Union (EU), the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), the United States, the Ukraine-Russia conflict, Syria, Kurdish autonomy and a multitude of other regional security concerns, including extremism and transnational terror.

Turkey’s Involvement in Ukraine-Russia Conflict

Following the outbreak of the Ukraine-Russia conflict, Turkey positioned itself as the key mediator between Kyiv and Moscow, balancing relations with both sides.

Erdogan and his government continue to supply weapons to Ukraine but have refused to place any sanctions on Russia. They also brokered the UN-backed deal that allows Ukrainian grain exports to pass through the blockaded Black Sea. Turkey has directly benefited from its neutrality, maintaining its strategic objectives of preserving and expanding their regional and international influence.

It is therefore unlikely that the upcoming elections will produce a significant policy shift in this regard. There would however be differences in how each candidate would pursue this role as mediator moving forward. Kilicdaroglu’s Turkey would likely continue to act as a mediator but has also stated that they would place more stress on Ankara’s status as a NATO member, potentially offering fewer concessions to Moscow. On the other hand, Turkey’s recent bilateral ties with Russia have likely been driven by the personal relationship between Putin and Erdogan, and a renewed mandate for the latter would likely strengthen these ties further.

Regardless of the election winner, an apparently weakened Russia is believed to be more susceptible to compromises and concessions in many fields of bilateral cooperation, including energy, agriculture, the South Caucasus, and Syria, with both Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu almost certain to leverage this as much as possible.

A difference in opinion towards NATO

One clear foreign policy difference between Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu is in relation to NATO and the accession of Finland, and the proposed accession of Sweden, to the organisation. After initially imposing a veto, Turkey agreed to Finland’s NATO membership in March 2023, whereas Kilicdaroglu immediately supported them joining the organisation. Erdogan however is still withholding support for Sweden’s membership, with it generally accepted amongst NATO members that he is doing this for domestic nationalist purposes. Opposingly, Kilicdaroglu and the NATION alliance supports Sweden becoming a member of NATO and say that it would be possible to confirm this by July 2023. If Erdogan is re-elected, it is likely that Sweden would still eventually receive accession, although delays to the process would have damaged Turkey’s relations with other NATO members, and therefore a Kilicdaroglu victory would likely foster better ties with NATO moving forward.

Complex Ties Between Turkey and the EU

Turkey was officially recognised as a candidate for full membership of the EU in December 1999, but progress was extremely slow and in February 2019 talks over their accession were officially suspended, with the EU accusing Turkey of human rights violations and criticising their deficits in the rule of law. This stand-off will highly likely continue if Erdogan is re-elected. Contrastingly, Kilicdaroglu and the NATION alliance would be likely to address this by liberalising reforms in the law, the media and the judiciary. Whilst the accession process would remain complex (there is anti-Western sentiment across the political spectrum in Turkey and certain members of the EU are sceptical of rekindling ties), a Kilicdaroglu win would likely deliver improved cooperation between Ankara and Brussels and would highly likely result in closer economic and security relations, particularly regarding migration.

Erdogan’s Increasingly Strained Relationship With the United States

Turkey’s relationship with the United States under Erdogan has been complex and increasingly strained. The last decade has seen substantial disagreements over the United States’ support for Kurdish forces in Syria, Washington’s alleged support for the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, and Ankara’s purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defence system.

The latter of these saw Washington remove Turkey from the F-35 jet fighter programme and place sanctions on the Turkish defence industry. The two nations have continued to cooperate on some matters, but an Erdogan victory would highly likely see this complicated relationship continue. Conversely, a meeting between the United States Ambassador to Ankara, Jeff Flake, and Kilicdaroglu in March 2023 likely suggests a different approach to Washington from the Turkish opposition. The meeting reportedly infuriated Erdogan who saw it as an intervention in the elections and pledged to “close the door” to Flake. Any initial moves to strengthen ties with Washington would align itself with his desire for closer ties to NATO, the EU and the collective West and therefore a Kilicdaroglu victory would likely see these relationships develop positively.

Ongoing Military Ties with Syria

Turkey has been involved militarily in Syria since July 2011, with Turkish forces occupying land in northern Syria since August 2016.

As a result, there has been a mass migration of nearly 4 million Syrians into southern Turkey, who are now battling a major cost-of-living crisis and are becoming increasingly hostile. For Kilicdaroglu and the opposition, Turkey’s role in Syria, and Ankara’s relations with Damascus, hinge on how they can address the issue of Syrian nationals living in Turkey.

Kilicdaroglu has pledged to create opportunities in Turkey and contribute to improving the conditions in northern Syria, to allow Syrians to return voluntarily. To allow this, Kilicdaroglu and a new Turkish government would likely be more eager to agree to a deal with Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad. Erdogan is also trying to establish a rapprochement, but Assad has said he will only meet the Turkish President when he fully withdraws his forces from Syrian territory.

Given that Erdogan is positioning himself as a strongman and being robust on defence and security issues, underscored by the May 2023 operation in northern Syria that killed the most recent leader of the Islamic State (IS) terror group, it is highly unlikely that such a withdrawal would materialise under his tenure. Consequently, an Erdogan victory would very likely preserve the current security situation in northern Syria.

Turkey’s long standing relationship with the Eastern Mediterranean region

Historically, Greece, Cyprus and the Eastern Mediterranean region have been fundamental to Turkey’s foreign policy. Turkey under Erdogan has pursued aggressive rhetoric in the region, with the latest issues centring around maritime borders and energy exploration rights in the Eastern Mediterranean, alongside alleged Greek militarisation of the Dodecanese Islands.

This latter issue is particularly sensitive and has been cited as justification for Turkish Air Force overflights and other reciprocal military escalations in the region. As recently as December 2022, Erdogan warned that Turkish missile systems were capable of striking Athens.

However, Greek support following the devastating February earthquakes and a visit by the Greek Foreign Minister, have eased tensions and provided hope for bilateral relations. It is likely Kilicdaroglu would seek to pursue positive relationships with neighbouring states, particularly Greece, whilst Erdogan would likely continue to adopt an outwardly hawkish stance towards Athens.

Future Forecast for Turkey

Turkish elections held on 14 May have historical significance. It was the election on 14 May 1950 that ended the one-party rule that the CHP had held since 1923. Turkey has held several elections since then, although the forthcoming elections are arguably the nation’s most important in decades, with some commentators arguing they could be the most critical since the establishment of democracy in the country. The Turkish population seemingly concurs, with current polls predicting a record voter turnout. Opinion polling suggests an extremely tight result for the presidential election, which will very likely require a run-off vote on 28 May with neither Kilicdaroglu nor Erdogan set to secure the 50 percent of votes needed to claim outright victory. Erdogan’s AKP are likely to win parliamentary elections, followed by the CHP. Such a closely run outcome will very likely create its own problems.

Political Instability Could Be a Catalyst for Mass Protests or Civil Unrest

A sizeable margin of victory for Erdogan or Kilicdaroglu would likely precede a peaceful transfer of power. However, a narrow margin of victory for either candidate would very likely prompt mass civil unrest and protests, with violence likely, and demands for a recount from the losing candidate.

How Erdogan and the AKP reacted to mayoral losses in 2019 is instructive in this regard. In Istanbul, after all of the votes had been tallied, opposition CHP candidate Ekrem Imamoglu achieved a narrow victory.

The AKP declared there were irregularities in the vote and evidence of “organised crime” which caused the Supreme Electoral Council (YSK) to rule in favour of a re-run that the opposition strongly objected to. Imamoglu won the re-run, although in 2022 he was subsequently sentenced to two years in prison and was barred from politics.

At every stage of this process, large-scale demonstrations occurred in support of both sides. There is a realistic possibility that the AKP and Erdogan could take similar actions if Kilicdaroglu wins. This scenario will almost certainly lead to widespread political volatility, demonstrations and unrest and given that Erdogan has stated that “you ride it [Democracy] as far as necessary and then step off”, it is unlikely that he would allow for a simple and non-volatile transfer of power to occur.

If the elections result in Erdogan remaining President, and the AKP performing well in the Grand National Assembly, expect a continuation of the Turkish domestic agenda and foreign policy witnessed since around 2015. It is almost certain that Erdogan would pursue his hardline, conservative approach of recent years, rather than the more progressive period when he initially took office. At home, Erdogan would likely continue to adopt unorthodox economic policy, alongside further persecution of the Kurdish minority. Internationally, Turkey would remain close to Russia, and Erdogan to Vladimir Putin, as well as likely continuing to aggravate the EU and US on matters of collective security policy. It is likely however that Ankara would still eventually agree to Sweden’s NATO accession.

An election result which produced a victory for Kilicdaroglu and the National Alliance would highly likely see Turkey roll back the vast majority of Erdogan’s domestic reforms of recent years, and return to a parliamentary system and secular republic. This would be done in haste alongside the removal of powers that Erdogan bestowed upon the role of president. Economically, policy is likely to shift quicker and more decisively towards a conventional fiscal plan. On the international stage, Kilicdaroglu would likely look to rehabilitate many of the relationships soured by Erdogan’s recent actions, and whilst highly likely wishing to maintain the nation’s key role as mediator in the Ukraine-Russia conflict, a much tougher approach to Moscow would be expected.

A Closely Run Race Between Candidates

Ultimately, the Turkish presidential election is highly likely to be closely run, and it is unlikely that either of the main candidates will reach the required 50 percent in the first round of voting.

In the most recent opinion polling, Kilicdaroglu leads Erdogan by a couple of percentage points, with both below the required 50 percent due to the presence of additional candidates – particularly Muharrem Ince. Ince is polling between three and seven percent, a level of support that if transferred to Kilicdaroglu would likely result in him securing the required 50 percent of the vote.

Kilicdaroglu’s best chance of winning comes by reaching victory in the first round too, because the support for the fourth candidate, far-right Nationalist Movement Party candidate Sinan Ogan, will almost certainly transfer to Erdogan in the run-off. Erdogan will likely settle for a run-off, as there is an increased possibility of his victory with this outcome.

However, if Kilicdaroglu does win the election, it is realistically possible that Erdogan attempts to retain power by inciting violence, indicating that civil unrest, demonstrations, and protests should all be expected to occur in its aftermath.

Intelligence reports,